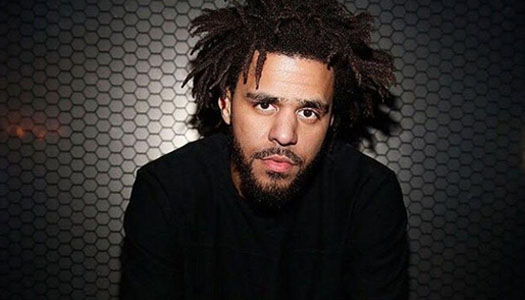

When J Cole announced the imminent arrival of KOD earlier this week, some of excitement was caused by the tracklisting: not the titles themselves so much as the fact that two of them seemed to feature a guest appearance, albeit from a hitherto-unknown artist called kiLL edward. The one thing everyone knows about J Cole is that his albums almost never feature special guests – after his album 2014 Forest Hills Drive broke a Spotify streaming record previously held by One Direction, the phrase “J Cole went platinum with no features” turned from endlessly repeated boast to internet meme.

One school of thought suggested the presence of kiLL edward was all an elaborate hoax, another that the “experimental” nature of his fifth album might include a slackening of his aversion to sharing space with others. It takes KOD a matter of minutes to announce that the latter is very wrong: “How come you won’t get a few features – I think you should?” Coles snaps on the title track. “How about I don’t? How about you just get the fuck off my dick?” And so it proves: kiLL edward turns out to be Cole himself, his vocals slowed down, the reverse of Prince’s helium-voiced Camille.

You can mock his fans’ bragging about the “purity” of his achievements if you want, but there’s also a sense in which Cole has become famous by doing exactly the opposite of virtually every other major contemporary hip-hop artist. Their albums sprawl towards the hour-and-a-half-mark, stuffed with appearances by special guests that sometimes seem to speak less of artistic fraternity and more of ensuring every commercial base is covered. His have increasingly clocked in at a crisp, old-fashioned 45 minutes.

As if to underline that J Cole albums come free of padding, KOD’s most emotionally impactful lyrics are on tracks labelled as interludes and outros, words that normally guarantee you won’t miss much if you hit fast-forward. Not here. The interlude Once an Addict turns out to be a heartbreaking, unsparing examination of his mother’s alcoholism and Cole’s own inability to intervene or help. The outro Window Pain concerns a child Cole met through his not-for-profit organisation the Dreamville Foundation, who attempted to make sense of her cousin’s shooting by suggesting it was all part of God’s masterplan, a signal that Jesus was coming back “so we can rejoice with him and have our time”.

Nor does Cole much bother with the kind of hook-laden banger guaranteed to ensure radio play and crossover pop success. Like its 2016 predecessor, 4 Your Eyez Only, the music on KOD is sparse and understated: even its most uptempo track, ATM, is set to muted, jazzy piano chords, while listeners of a certain vintage might find the term “trip-hop” springing to mind unbidden when the meandering guitar and vibraphone sample of Brackets slouch into life.

KOD’s sound exists in a curious, appealing area somewhere between beatifically stoned and slightly unsettling. Motiv8 revolves around little more than an eerie keyboard figure and a disembodied cry of “get money” from Lil Kim’s guest appearance on the 1995 Junior MAFIA hit of the same title – ripped out of context, it sounds bleak and despairing – and there’s something really haunting about Photograph, with its delicate two-note guitar sample and a chorus whose vocal appears to be slightly out of step with the beat.

This is an album on which Cole sets himself up as the conscience of mainstream hip hop – the goofy, self-deprecating humour of his 2014 single Wet Dreamz and the warm contentment of Foldin’ Clothes are both conspicuous by their absence. Instead, we find Cole repeatedly raising a concerned eyebrow at drug use in the world of Xanax-fuelled rap and probing hip-hop’s obsession with money. It’s the kind of thing that could come off a little preachy but it doesn’t here, largely because Cole is always quick to implicate himself. He has, he claims, “sipped so much Actavis I convinced Actavis that they should pay me”; while on ATM, he’s as guilty as anyone of allowing his wealth to define his self-worth. He’s also very good at unexpectedly flipping the script midway through a track. Brackets starts out sounding troublingly like a rich man moaning about having to pay tax, but ends up somewhere very different: an indictment of the inherent racism of US government spending.

But KOD’s best track may be its closer, 1985, which is billed as a taster of his forthcoming project The Fall Off. It delivers hip-hop’s new generations of artists (by whom Cole is “unimpressed”) a wise, warm but firm talking-to that switches from practical advice, warnings about the fleeting nature of fame and the inadvisability of jumping on trends to a stark and impressively incisive suggestion they should think hard about the nature of their appeal: “These white kids love that you don’t give a fuck, ‘cause that’s exactly what’s expected when your skin black… They wanna be black and think your song is how it feels”.

It’s clearly the stuff of which vast controversy is made – you can see the headlines about the rappers it’s addressing “clapping back” as it plays. But like the rest of KOD, it leaves you very eager to see where J Cole goes next. (Review Courtesy of Alexis Petridis)