Huge wealth disparities between Black and white households in America existed long before the COVID-19 pandemic and have continued during the crisis. Data show that during the pandemic, Black households faced more financial emergencies with fewer economic resources, resulting in a widening gap in economic opportunity between Black and white households.

This issue brief explores some of those data and discusses a variety of proposals to shrink the Black-white wealth gap. The Biden administration continues to propose bold, ambitious, and wide-ranging policies that would enable families to recover from this unique crisis as well as steer institutions and the economy in a more racially equitable direction. These measures are crucial to prevent the Black-white wealth gap from widening further. The Biden administration has taken the first, critical steps toward closing that gap: The recently enacted American Rescue Plan provided much needed financial relief to many struggling families, allowing them to build a small financial cushion for the ongoing recession. This financial relief was targeted at those struggling the most and particularly benefited Black households, as they have suffered disproportionately from the pandemic. Moreover, the legislation ensured that public sector jobs in state and local governments—which often provide a key pathway to middle-class economic security for Black workers—would return after steep losses during the pandemic.

Enacting President Joe Biden’s proposed American Jobs Plan would help create much needed jobs with good, stable wages and benefits across the economy, an important next step to help reduce racial wealth disparities. Additional federal policies should provide targeted financial benefits to African Americans, for instance, by boosting funding for the Minority Business Development Agency, financing for and targeting of federal research and development dollars to Black inventors and innovators, coordinated efforts at the White House to use federal programs, and policies and hiring to combat widespread and persistent racial wealth inequality.

In a matter of weeks, Black households, with little in the way of wealth or savings, were burdened with the severe financial demands that the coronavirus outbreak and subsequent recession placed on them. They were often faced with a choice that either exposed them to a virus with a disproportionate likelihood of severe complications compared with their white peers or lost them vital income at a time when unemployment was spiking to unprecedented levels and federal support was slow and infrequent.1

If people decided to stay home to protect their health and that of their families, they needed to rely in part on their savings to pay their bills. The data summaries below show that less access to savings not only made it more difficult for African Americans to weather unemployment and widespread health emergencies, it also meant that they could not support their children’s remote learning as schools closed buildings and went online, fund higher education plans when such plans were in greater demand, seek more stable and safer housing options, or maintain and grow their businesses to the same degree that white households could. At a time of greater financial need, African Americans had fewer resources to begin with. This left them especially vulnerable to the dual onslaught of a health and economic crisis. As the Great Recession showed, without an explicit long-term focus on racially equitable economic policies, the disparities that predate the crisis will persist or continue to grow.

The federal government plays a crucial role in bringing the economy out of recessions and in addressing the economic inequities that exacerbate the fallout from these economic downturns in the first place.

To help tackle this challenge, the Center for American Progress’ National Advisory Council on Eliminating the Black-White Wealth Gap developed several proposals.3 The council included some of the country’s leading scholars on the Black-white wealth gap, who assisted CAP’s effort to identify novel, yet doable, policy steps to shrink and eventually eliminate this racial disparity.

CAP’s work with the council provides useful policy lessons. Importantly, even if all such proposals were immediately enacted, a substantial wealth gap would remain, requiring additional measures. Moreover, it will take time, even with the implementation of these proposals, to shrink the Black-white wealth gap. Put differently, policymakers need to act quickly and decisively, in a targeted manner and for a long time, to eliminate the racial wealth gap.

The benefits of such an effort are clear: Supporting wealth-building measures for communities of color, in particular, would give families the resilience for the inevitable economic shocks that the future will bring, while also boosting growth in ways that are tangible for workers in every sector of the economy. These measures could result in a shrinking wealth gap between Black and white households. By raising the wealth of African American households, U.S. society and economy would become more resilient; a fast-growing share of the population would be better prepared for future emergencies and have more resources available to shape its own future. More wealth for African Americans thus not only represents a step toward greater racial equality but also lays the foundation for stronger economic growth. For instance, Black households would have more opportunities to contribute their talents and skills to the economy, move to better jobs when such opportunities arise, encourage their children’s education, and maintain and grow their own businesses.4

President Biden’s focus on reducing racial inequities will thus pay long-term dividends in a number of ways. Enacting proposals, such as the ones from CAP, that target small-business development and research and development—and that would establish a federal policy infrastructure to combat persistent racial wealth inequities—is a key next step to substantially shrinking the Black-white wealth gap.

Black households had fewer emergency savings to fall back on during pandemic

The pandemic occurred against the backdrop of a massive Black-white wealth gap. Because households quickly needed to rely on their wealth when the pandemic hit in early 2020, the crisis also illustrated the importance of wealth for families’ financial security. Black households suffered more in the pandemic in large part because they needed more but had much less wealth than white households. Wealth, both as an emergency buffer and as a means to invest in people’s futures, became critically important.

Millions of households, especially African American and Latino households, faced unemployment and multiple health emergencies more or less from one day to the next. Yet many of these same households had few or no emergency savings to fall back on during this time. When people lost their jobs, many needed to rely on emergency savings, leaving them with less financial security as the pandemic unfolded. For example, in 2020, 46.7 percent of unemployed white households could not come up with $400 in an emergency, while 65.2 percent of unemployed Black households lacked access to $400 in such situations.5

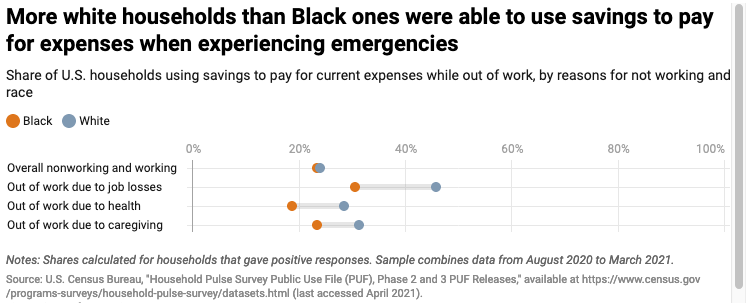

Many more white than Black households could use their savings during the pandemic to fill any financial gaps left by job losses and/or higher health care costs. This disparate reliance on savings to pay for current expenses reflects the highly unequal distribution of emergency savings by race.6 After all, households that had no or few emergency savings could not use them to help pay their bills after a job loss. While 45.9 percent of white households that saw a drop in job-related income used their savings to pay for current expenses, only 30.6 percent of Black households did so. (see Figure 1) Similarly, more white households than Black households—28.5 percent versus 18.8 percent—used their savings when they were out of work due to health reasons. When households actually needed to rely on their savings, fewer Black households than white households had the opportunity to do so, even though many more Black households experienced layoffs and health emergencies during this time.

Figure 1

Even if they could not fall back on savings, Black households still needed to fill the gap in their finances left by job losses and higher health care costs. They often did so by borrowing more money.7 For example, 44.5 percent of white households that used savings to pay for expenses also borrowed on credit cards, and 16.1 percent borrowed from family and friends; this suggests that they did not have enough emergency savings. In comparison, many more Black households in this situation borrowed money, with 45.8 percent taking out loans and 28.5 percent borrowing from family and friends. Essentially, Black households substituted more debt for limited emergency savings, widening the wealth gap between typical Black and white families.

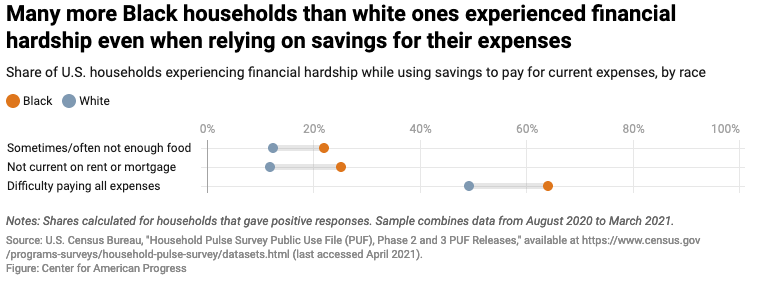

Even when Black households used their savings to pay for expenses, they were more likely to experience financial hardships amid the pandemic. This suggests that Black families’ savings were often not enough to allow them to handle the many job, child care, and health care challenges that arose during the pandemic. African Americans that used their savings to pay for current expenses were more likely than white households to sometimes or often not have enough food, to not be current on their rent or mortgage, and to have difficulties paying all of their bills. (see Figure 2) For instance, 64.1 percent of African Americans who used their savings to pay for expenses had trouble paying all of their bills, and the same was true for only 49.2 percent of white households. (see Figure 2) Having savings to pay for expenses during emergencies was clearly not enough to avoid economic hardships for all households, but the chance of still experiencing such hardships was much higher for Black households than for white ones.

Put differently, Americans generally have too few emergency savings, but this shortfall during the pandemic was much worse for Black households.

Figure 2

The bottom line is accessing savings to fill the gap left by too little income among widespread economic emergencies is not enough to avoid economic hardship and future hardship as debt grows, especially among Black households.

The pandemic laid the foundation for greater wealth inequality in the future

The racial wealth gap also manifests in disparities in long-term investments, and not just in differences in emergency savings and immediate financial insecurity; during the pandemic, Black households had less wealth and thus fewer opportunities to invest in education, homeownership, and business stability or to choose to retire amid a worsening labor market. Yet the pandemic was a time when families often needed to spend more money on education—for example, to support their children’s remote schooling or to pursue postsecondary education to boost their own earning potential in the face of a highly uncertain future in the labor market.

During this time, many households also sought housing stability and explored new housing options to protect their health and that of their families. Moreover, many household members who owned their own business needed to access savings to keep their business running as they either were forced to shut down or saw demand for their goods and services drop amid customers’ health concerns. Inevitably, the labor market quickly worsened, often pushing older Black workers in particular out onto the unemployment line.

While Black families often had greater needs to invest in education, housing, and businesses or to move into retirement, they had fewer resources to do so at the start of the pandemic. The result has been widening gaps in key long-term investments—such as education, housing, business ownership, and retirement—between Black and white households.

Impact on education

For example, during remote schooling, Black households faced greater obstacles in helping support their children’s education. All households needed money to ensure that their children had reliable internet and regular access to the appropriate electronic devices available when schools moved to remote instruction. Yet Black households were less likely than white households to have savings and were more likely to exhaust those savings, as discussed above. This left them with less money to support their children’s education. For this reason, these households often ended up borrowing money from family and friends to pay for current expenses. Indeed, Black households were almost three times as likely as white households—22.4 percent versus 8.5 percent—to borrow from family and friends to pay for current expenses.8

This greater reliance on financial assistance from family and friends also correlates with less access to internet and device availability since Black households’ finances were stretched particularly thin. More than one-fourth of Black households—27.6 percent—that borrowed from family and friends did not have access to reliable internet services and electronic devices during remote schooling, from August 2020 to March 2021. In comparison, only 6.4 percent of white families who paid for expenses out of their current income lacked reliable internet and electronic device access, as did 11.2 percent of white households that used savings to pay for expenses.

Since Black families had less money and greater financial needs during the pandemic, they were left with even less money to support their children’s education.9 These racial gaps in instructional resources can quickly translate into longer-term differences in educational achievement and thus contribute to persistent racial wealth disparities across generations.

The data show a similar pattern related to postsecondary education plans—or certification and degree programs. Today, nearly two-thirds of jobs require some form of postsecondary education, yet among Black households that borrowed from family and friends, 43.9 percent canceled their postsecondary plans, and another 12.9 percent decided to take fewer classes.10 In comparison, 29.1 percent of white households that mainly used their income for expenses decided to cancel their postsecondary plans, and another 10.1 percent decided to take fewer classes. Again, less access to emergency savings often translates to more borrowing from friends and family, fewer future opportunities, and less economic mobility for Black households, compared with white households.

Obstacles to homeownership

The fortunes of Black and white homeowners also diverged during the pandemic. A much larger share of Black homeowners than white homeowners—17.6 percent versus 6.9 percent—fell behind on their mortgage from August 2020 to March 2021.11

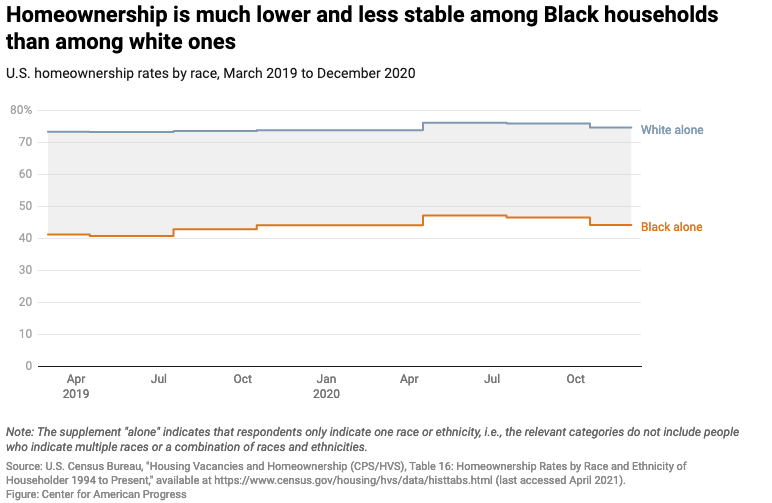

Not surprisingly, then, homeownership among African Americans grew more slowly than it did for white households during the pandemic, despite historically low mortgage interest rates. The Black homeownership rate stood at 44.1 percent by the end of 2020, almost equal to the 44 percent rate at the end of 2019. In comparison, the white homeownership rate rose from 73.7 percent to 74.5 percent during the same time period. (see Figure 3) Simply put, Black households faced more obstacles to becoming and staying homeowners because they had less money to fall back on.

Figure 3

Moreover, Black homeownership saw wild up-and-down swings throughout 2020. The Black homeownership rate quickly rose by three percentage points in early 2020, before falling by 2.9 percentage points. Meanwhile, the white homeownership rate grew initially by 2.3 percentage points, before declining by only 1.5 percentage points. (see Figure 3) In other words, homeownership was much more stable among white households than Black households during the pandemic. This greater housing instability for African Americans follows in part from less stable jobs, more debt relative to the value of houses, and fewer emergency savings outside of the house to pay for an emergency. In other words, economic emergencies such as layoffs or unexpected medical bills more quickly translated into housing instability and, possibly, the loss of a home for Black homeowners than for white homeowners.12

A toll on retirement

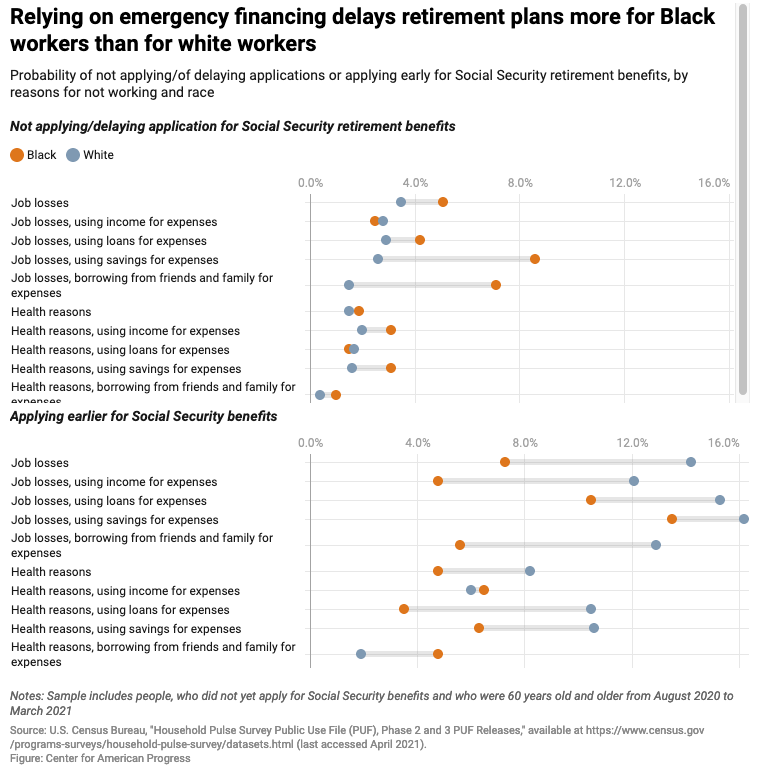

Finally, during the pandemic, older Black workers—those aged 60 and older—were more likely than their white counterparts to delay retirement after a job loss and dip into their emergency savings. For example, 8.6 percent of Black workers that experienced a pandemic-related job loss and used their savings for expenses decided not to apply or to delay applying for Social Security retirement benefits, compared with only 2.6 percent of white workers. (see Figure 4) Similarly, 7.1 percent of Black workers who lost their job and borrowed money from family and friends to pay for expenses delayed retirement, compared with only 1.5 percent of white workers.

A similar pattern by race, albeit at smaller rates, exists among older workers who were out of work due to health reasons. As is often the case during a recession, older workers in 2020 retired or planned on retiring sooner than they had expected before the coronavirus-induced recession. However, older Black workers were less likely than their white counterparts to retire or plan on retiring early during the pandemic. For instance, 5.6 percent of older Black workers who lost their job and who borrowed money from family and friends decided to retire sooner than planned, compared with 12.9 percent of older white workers. (see Figure 4) Older Black workers were much more likely than older white workers to delay retirement and were less likely to retire early, instead relying on emergency financing. This suggests that relying on savings and borrowing also disproportionately depleted Black workers’ retirement savings and delayed their retirement plans.

Figure 4

Stark wealth differences left Black households especially vulnerable to the health and economic crisis

The larger short- and long-term financial vulnerabilities of Black households during the pandemic occurred in the context of a persistent and wide racial wealth gap.13 When the pandemic and recession started in early 2020, Black households had less wealth than white households but greater need for the safety that those resources provide. In 2019, Black households, on average, had 14.5 percent the wealth of the average white household, and the median wealth of Black households was 12.7 percent the median wealth of white households that year.14 The pandemic hit Black households harder than white households and likely further widened the wealth gap among a large share, if not most, of Black and white households.

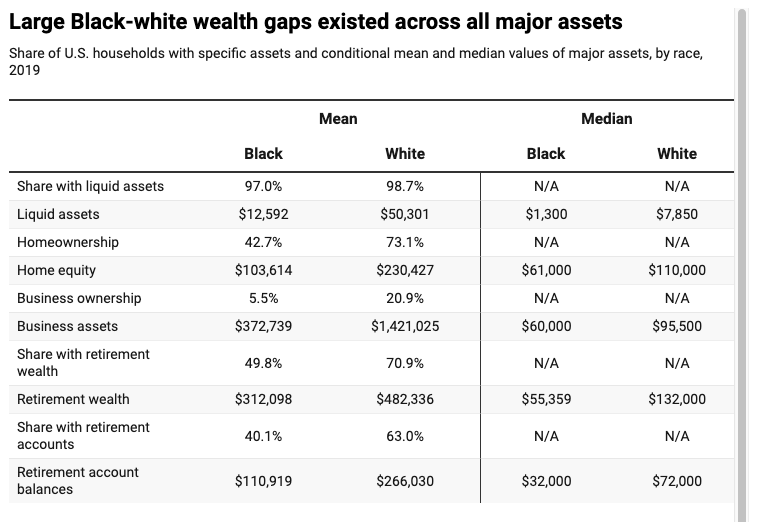

Further breakdowns of the data by different types of assets such as emergency savings, housing, business ownership, and retirement wealth underscore the large Black-white gaps in all of these areas. For one, other than with respect to liquid assets—such as checking accounts, savings accounts, and money market mutual funds—Black households were much less likely to own assets. For example, only 5.5 percent of African-Americans owned a stake in a private business, compared with 20.9 percent of white households. (see Table 1) Black households are also less likely to be homeowners, as already discussed; and only about half of all nonretired Black households with a respondent aged 25 years or older had a retirement account, compared with 70.9 percent of white households meeting this description (see Table 1).

In fact, when it comes to simply owning a bank account, there are significant disparities. Black people were unbanked at a rate five times higher than that of their white peers before the pandemic, with less than half of all Black adults having the full suite of financial service associated with a bank account.15 Such a barrier makes it harder for Black households to build wealth at the same rate as white households.

Table 1

Even when African Americans own such assets, they own much less of them. In 2019, Black households, on average, had one-fourth the liquid assets of white households: $12,952 compared with $50,301. (see Table 1) The gap at the median is even worse, as Black households had only $1,300 in liquid savings—the equivalent of 16.6 percent of white households’ median balance of $7,850. Therefore, Black households were typically much less prepared for the pandemic and the myriad financial emergencies it created, including layoffs, caregiving needs, and worsening health outcomes.

Black households also had much smaller home equity, retirement account balances, and business values than white households. For example, African Americans had, on average, less than half the home equity of white households in 2019: $103,614 compared with $230,427. (see Table 1) Similarly, the average retirement account balances of Black households—$110,919—equaled 41.7 percent of the average balance of $266,030 for white households that year. The gap is especially large with respect to business equity, as the average worth of African Americans’ businesses, $372,739, equaled only 26.2 percent of the average value of white households’ businesses, or $1,421,025.

For one, these differences in asset values laid the foundation for greater losses among many African Americans during the pandemic. Lower values of businesses and home equity often result from higher debt levels relative to the underlying assets. On average, mortgages accounted for 41.4 percent of Black homeowners’ house values in 2019, while they made up only 32.6 percent of white homeowners’ house values.16 A larger ratio of mortgages to home values also means that Black homeowners carried a larger debt burden into the pandemic. This fixed cost added to their financial stress when incomes quickly dropped, especially for Black workers, who were more likely to work in industries and occupations that were immediately affected by the coronavirus crisis.17

Moreover, fewer long-term assets meant that Black households had fewer choices in the labor market when jobs quickly disappeared. Older Black workers had fewer retirement assets and thus faced more pressure to remain in the labor market, even as they faced much higher unemployment rates than did their white counterparts. For instance, the unemployment rate for Black workers between the ages of 55 and 64 averaged 10.8 percent from March 2020 to June 2020, the first four months of the pandemic, and 9.1 percent from July 2020 to December 2020, up from 3.6 percent for all of 2019. In comparison, the unemployment rate for older white workers averaged 8.5 percent at the start of the pandemic and 5.9 percent during the second half of 2020.18

With less retirement wealth to fall back on, Black workers faced and will continue to face greater pressure to remain in the labor market, even at times when jobs are hard to come by.

Policy responses have started to meet the generational challenge of closing the gap

Just 100 days into the Biden administration, Americans began to see encouraging signs that he is prepared to lead the country out of the largest crisis of their lifetime in a way that will improve the lives of millions in both the short and long term. Moreover, the Biden administration has taken a number of steps that start to address the massive Black-white wealth gap in this country. Of course, much work remains to be done. This issue brief lays out several metrics related to household wealth inequality that show the disparities before and during this pandemic.

Given the sheer size of the Black-white wealth gap, it will take a wide range of policy measures across an extended period of time to eliminate this disparity. Importantly, policy measures will need to provide direct targeted financial transfers to African Americans to overcome their inherent wealth disadvantages across generations. Black households are much less likely than white households to inherit money or receive large financial gifts from parents and grandparents; and when they do receive such intergenerational transfers, the amounts tend to be much smaller.19

Yet money transfers alone will not close the Black-white wealth gap. African Americans regularly encounter a wide range of obstacles in building wealth at the same rate as white households.20 These include, for instance, discrimination in labor markets, housing, credit markets, and health care, as well as segregated neighborhoods that offer fewer health care, education, and food services and amenities. This all leads to slower growth in housing values. Reducing and eventually eliminating the Black-white wealth gap would therefore also require the implementation and enforcement of systematic anti-racist policies in all key markets.

President Biden has signed several executive orders that represent a crucial first step toward greater racial equality. For example, his executive order on “Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government” takes a number of steps that could result in more equitable treatment by and access to the federal government.21 Agencies are required to conduct a review of equity among their employees, policies, and programs and come up with a plan within 200 days to reduce obstacles to opportunity. The executive order also requires the U.S. Office of Management and Budget to identify areas where the federal government could use its money to invest in underserved communities. Finally, the executive order creates an Equitable Data Working Group that would examine and come up with suggestions to address shortcomings in federal data collection.

The combination of these efforts will make it easier for the federal government to take a lead on creating more opportunities for African Americans to apply for and participate in a wide range of federal employment and programs. Even still, reorienting the federal government toward greater racial equality is only one of many policy steps necessary to create a truly level playing field for African Americans.

The Black-white wealth gap will not shrink or disappear for a long time. It will require a sustained commitment from the federal government as well as private employers and communities. The final publication of CAP’s National Advisory Council on Eliminating the Black-White Wealth Gap highlighted this generational challenge.22 The council included many of the country’s leading experts on the Black-white wealth gap, its history and contributing factors, and existing policy proposals to eliminate this disparity. These experts met over the course of 2020 to discuss and develop a range of new policy proposals that could go a long way to solving the issue.

The discussions and work of the council highlighted the challenges in eliminating the Black-white wealth gap: Disparities will continue into the future if there is not decisive, persistent, large-scale, and targeted efforts to eliminate this wealth inequality. To be clear, policymakers will need to enact measures that provide unrestricted and substantial financial assets to African Americans, in addition to pursuing policy proposals such as those identified by the council to completely eliminate the wealth disparity.

After all, policy has to correct for the fact that white families have been able to accumulate and pass on wealth from generation to generation, for decades and centuries. At the same time, enslaved Africans were the source of such wealth for many white households, and African Americans were later consistently prohibited, often violently, from accumulating wealth. Eliminating the Black-white wealth gap is thus a generational policy challenge.

The council provided several examples of policies that could be enacted and would contribute to a smaller racial wealth gap.23 These proposals build on other key proposals from the Center for American Progress to facilitate equitable wealth generation—for instance, in the areas of retirement savings and homeownership. While the council’s proposals are specifically targeted at shrinking the Black-white wealth gap and supporting wealth generation among African Americans and other households of color, these additional proposals offer benefits to many groups of households.

Improving access to unbanked and underbanked households through postal banking

Experts both on the council and at the Center for American Progress proposed the creation of a postal banking system.24 Part of the challenge of building wealth is that African Americans often have less access to low-cost, low-risk banking services and thus end up more likely to be unbanked or underbanked. Yet postal banks would address this challenge since there are post offices in all communities. Moreover, postal banking would quickly reach a meaningful size, which would keep costs low for financial services. And the government would provide the necessary backstop to ensure that savings held through the postal banking system were safe.

Increasing access to federal research and development funding for Black innovators and inventors

With the unveiling of the American Jobs Plan, President Biden has committed to “eliminate racial and gender inequities in research and development and science, technology, engineering, and math.”25 Indeed, historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), as well as Black innovators and inventors, regularly receive much less funding for their research and for bringing innovative products to market.

The Biden administration could take additional steps to boost Black researchers, innovators, and inventors.26 First, the federal government should substantially increase its commitment to finance research and development (R&D). Second, federal agencies should ensure that Black innovators and inventors, HBCUs, and predominantly Black communities get equitable access to federal R&D funding. Third, the federal government should create an innovation dividend—a regular payment derived from federally funded research and development—that is targeted to Black households. This innovation dividend could be funded through a number of mechanisms, such as auctioning off licenses and copyrights or equity stakes in innovative ventures created with federally funded R&D. Such an innovation dividend could be paid out as regular cash payments or in the form of debt-free college attendance, among other options.

Providing additional support for Black entrepreneurs to start and grow their businesses

The Biden administration has already committed to small-business incubators and innovation hubs to boost entrepreneurship in communities of color—a crucial first step. On June 21, 2021, the White House announced efforts to increase federal contracting with small disadvantaged businesses by 50 percent, which is the equivalent of an extra $100 billion over five years.27 The White House also announced that it included $31 billion in small-business programs in the American Jobs Plan. This investment will make it easier for Black businesses to obtain capital, access networking and mentoring through federal contracts, and gain funding for federal research and development.28

The Biden administration could build on these steps. Robust support for the Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA), as previously proposed in a CAP report, 29 could work in tandem with these efforts to ensure that business creation is not limited by the availability of intergenerational wealth.

The CAP proposal suggested additional funding for the MBDA. These additional resources could be used to start an economic equity grant program that could support municipal projects to boost wealth generation. The additional funds could also start a business center initiative at minority-serving institutions to run business incubators and accelerators, which in turn would offer startup capital as well as technical and legal assistance and other necessary support for those wanting to start and grow a business. Moreover, the added funding could be used for an office of research and evaluation that studies, among other things, the systematic barriers that people of color face in starting and growing their businesses as well as policies and programs that can overcome these barriers. Further, the MBDA could provide low-cost, government-backed capital to qualifying minority business investment companies. It could also create an office of advocacy and intergovernmental affairs to advance the economic and business interests of minority-owned small businesses.

Establishing greater access to retirement savings through a national saving plan

Black families have far fewer retirement savings than white families. They are less likely to be covered by a retirement benefit at work, and even when they participate in such a retirement plan, they save less for retirement due to lower earnings and greater income instability.

Public sector work provides an important pathway for African Americans to gain access to both middle-class careers and retirement benefits.30 Beyond the public sector, however, African Americans face much greater obstacles than white workers in saving for retirement.

Ensuring equal access to retirement security for African Americans, then, requires both protecting public sector jobs and giving African Americans greater access to retirement savings in the private sector. The American Rescue Plan provided much needed fiscal relief for state and local governments.31 It included $360 billion in emergency funding to help bring back much needed investment in public employment, which saw the loss of more than a million public sector jobs during the early stages of the pandemic.32 Thanks to this landmark legislation, state and local governments will be able to maintain vital public services. And African-American households will continue to have access to meaningful pathways toward middle-class financial security.

In addition, policymakers at both the federal level and the state and local level can do more to give all workers that do not yet have access to retirement savings—many of whom are people of color—a chance to save for retirement. CAP’s proposal for a National Savings Plan provides a blueprint for such a state-sponsored retirement savings plan,33 under which all workers would have the opportunity to effectively build wealth for retirement. Since African Americans are much less likely than white workers to currently have access to a retirement plan at work, the creation of the National Savings Plan would especially benefit Black workers.

Investing in early childhood care and education to lower costs and increase income stability

The pandemic has starkly illustrated the need for investments in early childhood education. The Biden administration—with the passage of the American Rescue Plan and the introduction of the American Families Plan—has shown it understands that equity and growth go together.34 Access to high-quality, affordable child care is a powerful tool for achieving racial and economic equity in the aftermath of the pandemic and beyond.35 Affordable, quality child care gives families a chance to pursue their careers and save for their future. Yet African Americans often face costly child care options.36

The American Rescue Plan provided $39 billion in child care relief, including funds for child care providers that struggled due to the pandemic.37 If enacted, the broader funding associated with the American Families Plan would increase access to paid family and medical leave as well as early childhood care and education for underserved families.38 African Americans, Latinos, many Asian Americans, and Indigenous workers lack those crucial benefits, making it more difficult for them to save for the future, among other things. However, if enacted, the measures proposed in the American Families Plan would help close racial gaps in access to such crucial benefits, as parents would face lower costs and greater income stability.

Providing financial support for higher education to shrink the wealth gap through lower debt burdens and higher career earnings

Making a college education tuition- and debt-free can be an important aspect of shrinking the Black-white wealth gap.39 The American Families Plan, if enacted, would prove a crucial step toward equalizing access to higher education by making two years of community college free, increasing Pell Grants for low-income households by $1,400, and offering two years’ worth of subsidized tuition and expanded programs in high-demand fields at HBCUs and other minority-serving institutions.40 These will be crucial first steps to give all students, especially students of color, equal access to higher education and thus a means to build wealth.

The Biden administration could expand these efforts. Experts at CAP have proposed and supported a number of steps that could go a long way toward making college tuition- and debt-free.41 These include $10,000 in universal loan relief for all college borrowers. Additional steps could include doubling the maximum Pell Grant amount, which would help cover out-of-pocket living—or nontuition—expenses, especially for students from low-income backgrounds. Moreover, the federal government should make additional investments in HBCUs, other minority-serving institutions, and community colleges.

Increasing homeownership and protecting housing assets from climate change

The Biden administration has rolled out several affordable housing initiatives and proposals. The president ordered the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to examine recent regulatory actions by the Trump administration in order to evaluate their impact on HUD’s ability to administer and enforce the Fair Housing Act (FHA).42 This order occurred within a week of the new president taking office, highlighting Biden’s emphasis on the need for equal access to homeownership. The administration followed this rule by reinstating the majority of the 2015 Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule. This rule will encourage local jurisdictions to better enforce housing discrimination protections and provide them with the resources to do so.43

President Biden also included $213 billion for affordable housing investments in his jobs plan. This money would go to developing, maintaining, and retrofitting affordable housing units over a period of eight years.44 The American Jobs Plan also includes a proposal for $5 billion in grants to state and local governments that would end exclusionary zoning laws.45 This could make it easier for Black families to gain access to homeownership in communities that have long used such laws to exclude them.

On June 1, 2021, the White House further elaborated on details of the American Jobs Plan. It proposed to include a $10 billion Community Revitalization Fund; $15 billion in new grants and technical assistance to support the planning, removal, or retrofitting of transportation infrastructure; a new neighborhood homes tax credit; and $5 billion for the Unlocking Possibilities Program to boost affordable housing.46 At the same time, the White House also announced an interagency effort to address inequity in home appraisals, which has made it harder for communities of color to secure affordable financing.47 The new administration has started to lay a path toward greater racial equality in homeownership through regulatory actions and spending proposals.

The Biden administration could still build on these promising proposals to ensure that Black homeowners can see equitable increases in the value of their houses. CAP’s Michela Zonta, for example, has put forth and supported several proposals in her work:48

- Local jurisdictions should once again become responsible for planning to achieve fair housing; the AFFH rule should thus be fully reinstated.

- Congress should provide more funding for the Fair Housing Initiatives Program and for staffing in HUD’s Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity. This would empower federal, state, and local governments and nonprofits to fully enforce the FHA.

- HUD should firmly enforce the FHA’s disparate impact rule.

- Financial regulators should take environmental factors into account in their Community Reinvestment Act examination criteria. This would increase investments in communities of color that face critical challenges related to climate change and environmental racism.

Conclusion

Addressing the persistent and large wealth gap between Black and white households is one of the biggest challenges facing racial equality in America today. Shrinking—and eventually eliminating—this gap would create more and better economic opportunities for all Americans. Families would gain financial security and be better positioned to take advantage of economic opportunities. Communities would become stronger with more and more equitably distributed jobs. And the economy would grow faster because many Black households would be better able to contribute their skills and talents where they are desperately needed.

President Biden’s large-scale policies and proposals, if enacted, are a meaningful first step in the right direction. Yet there are a number of additional steps that the administration and Congress could take to tackle this pressing issue. Black families’ lack of financial security and opportunity deserves even more attention and sustained momentum over the coming years and decades.

The Center for American Progress is an independent nonpartisan policy institute that is dedicated to improving the lives of all Americans, through bold, progressive ideas, as well as strong leadership and concerted action. Our aim is not just to change the conversation, but to change the country.

Christian E. Weller is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and a professor of public policy at the McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Richard Figueroa is a research associate at the Center.

The authors are grateful to Nicole Lee Ndumele, Mara Rudman, Michela Zonta, Erin Robinson, David Madland, Charlotte Hancock, and Anthony Marshall Jr. for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this issue brief.