On Tuesday, it announced that Lisa Borders, an African American woman who most recently helmed the Women’s National Basketball Association, will be the group’s first president and CEO. But from the beginning, the organization said its mission was to assist all women. In a posted “letter of solidarity,” the group voiced support for its “sisters” in industries ranging from housekeeping to factory work.

“To every woman employed in agriculture who has had to fend off unwanted sexual advances from her boss,” it read, “every housekeeper who has tried to escape an assaultive guest … We stand with you. We support you.”

Alianza Nacional de Campesinas, a national farm workers alliance wrote the first letter of unity, addressed to the Hollywood community, and was involved in the planning of the initial Time’s Up campaign, says Alianza co-founder Monica Ramirez.

“There was a very clear call to action by women of the entertainment industry,” Ramirez says. “They made the decision that to solve the problem, we needed to link arms across industries.”

It is the media’s focus, many contend, that has been one-sided.

“So much of the power of the MeToo movement comes from … the public outing” of some high profile harassers and equally well-known accusers, says Gonzalez. But there’s less interest “when you have workers that quite frankly, people don’t care as much about. And you have employers that nobody’s heard of, or supervisors and companies that nobody’s heard of. It just doesn’t have the same … appeal for the broader media.’’

But just as it was a black woman, Tarana Burke, who launched the MeToo hashtag and movement to much less fanfare more than a decade ago, it is black women who are among those most in need of any gains that the movement makes.

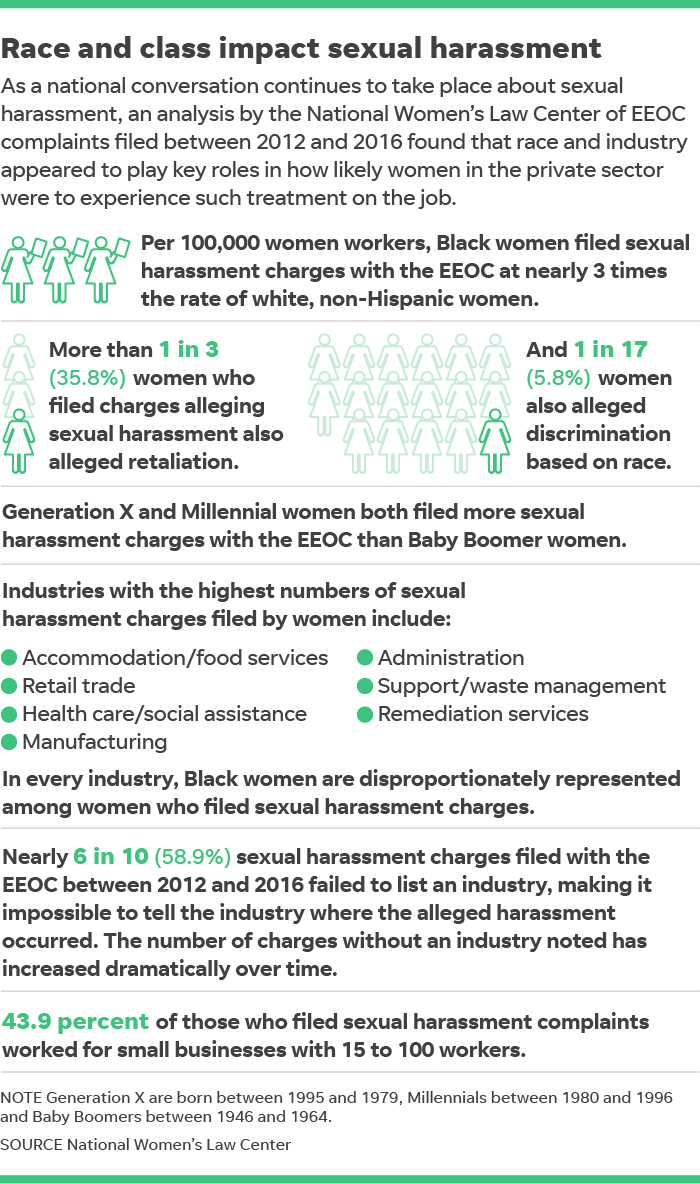

“There has not been enough attention to the way sexual and racial harassment intersect, and the ways a woman’s racial identity can target them for harassment,” says Emily Martin, vice president for education and workplace justice at the National Women’s Law Center.

An analysis by the National Women’s Law Center of complaints filed between 2012 and 2016 with the EEOC found that black women working in the private sector lodged sexual harassment charges at nearly three times the rate of white women.

A study by the workplace culture and compensation monitoring site Comparably similarly found that African Americans had the highest rate of being sexually harassed, with 24 percent saying they experienced such mistreatment on the job.

Among those filing sexual harassment complaints, “black women are over represented compared to their share of the workforce in every industry,” Martin says, ” pretty clear evidence that there is a difference in the levels of experience of harassment.’’

That is likely because black women face what sociologists have dubbed double jeopardy, bias and mistreatment exacerbated by their race as well as gender. “Harassment is an exercise of power at work,” says Martin, “so if you are a woman and black, that’s two markers of relative powerlessness in that workplace hierarchy, and they compound each other.”

For black women in lower wage jobs, the situation can also be magnified based on class. All of those factors can make a harasser believe ” ‘I can get away with it,’ ” Martin says. “

Burke founded the MeToo movement in 2006 initially to address the sexual violence inflicted upon black women and girls.

“It’s clear that if I don’t call out their needs by name, that everyone will not understand the nuances and specific needs that our different communities have,” says Burke who also notes the particularly high rate of sexual violence experienced by Native American women.

Fight has been going on longer than #MeToo

Like Burke, advocates for women of color and those working on farms, in hotels and in other working class jobs say they have been sounding the alarm on sexual harassment, . Still, MeToo has presented an opportunity to usher in change faster.

“We often say with pride that our janitors said basta (enough) before anyone said ‘me too,’ ’’ says Gonzalez who introduced a bill two years ago that focused on abuse in the janitorial industry.

But this year, as MeToo gained momentum, Gonzalez introduced several more bills with the thinking that “the MeToo movement (would) provide us this voice and this opportunity . . . a headwind to get some of these long-term issues we’ve been working on” addressed.

Though California’s Governor Jerry Brown vetoed several of Gonzalez’s proposals, he did sign off on legislation that will require the creation of a policy to address and track sexual harassment faced by home health care aides by Sept. 30 of next year.

A broader movement to improve wages and work conditions is also underway, an effort that activists say is especially critical to protect those who are the most financially vulnerable from sexual abuse.

The National Women’s Law Center found in its EEOC analysis that among sexual harassment complaints in which an industry was noted, the largest share – roughly 14 percent — was made by women working in food services and the hospitality sector.

When several McDonald’s employees filed sexual harassment complaints with the EEOC in May, their actions spurred the creation of women’s committees within the Fight for $15 movement, which is focused on raising the minimum wage.

Committee members then put in motion a strike that led McDonald’s crew members in ten cities, to walk out in protest of what they said was the company’s inaction in dealing with harassment, ranging from groping to requests for sex, in its restaurants. The Fight for $15 has also set up a #MeToo McDonald’s hotline that employees can call to get free legal guidance.

If “your paycheck is the only thing standing between your family and homelessness next week, it’s much easier (to be coerced by) someone sexually.” says Martin. “The McDonald’s strike … is a great example of workers organizing and most of the individuals that brought the EEOC claims against McDonald’s as part of that movement are women of color.’’

The hospitality industry has also taken steps to better protect workers, efforts that began before MeToo, but which have gotten more attention in the current cultural moment. While hotels in several cities, including Chicago, Seattle and New York, already make sure workers have access to personal alert devices to protect them from sexual assault and other crimes, several of the largest hotel chains committed last month to distributing those devices industry wide by 2020.

They are urgently needed, says Juana Melara, who has spent years cleaning rooms in hotels.

She has many stories. A very common scenario is a guest asking for a massage, or staying in the room while the housekeeper cleans and starting a conversation that quickly crosses the line.

“As things go on they start with personal questions, like if you’re happily married, what do you do after work,” says Melara.

One of her most frightening experiences occurred several years ago when a man exposed himself to her at the hotel in Cerritos, California. where she worked. “The only thing between me and him was the cart that had the supplies I needed to clean the room,” she recalls. The hall was empty, but she yelled, and the man, who she believes was actually not a guest, left. “I was scared that he was going to come back.”

Around that same time, Melara says a guest attempted to rape one of her co-workers. Though cell phones were not very common, her husband insisted that she get one. He said “don’t leave it in your locker. Carry it at all times because if that happened to her, that could happen to you.”

She stayed at that hotel for years, before getting her current job in 2014. ” I always reported. I wasn’t quiet at all, but I never got anywhere,” she says of the harassment that she endured. And when she speaks to her former co-workers, conditions at that particular seem even worse. “That’s why we fight so hard… They’re just trying to earn a living for their families without knowing if they’re going to return at the end of the day to see their family members.”

Lorena Lopez, an organizing Director for Unite Here Local 11, the Los Angeles affiliate of the North American hospitality workers’ union says that there have been industry players who have fought efforts by advocates to make sure safety devices are offered in a range of properties, and organizations like Time’s Up she believes are not in touch with her members’ struggles.

“We have to do it on our own,” Lopez says. “They don’t understand the issues of working women . .. The risk is a hundred times more than what celebrities risk.”

But among the more than 3,500 men and women who’ve contacted the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund for assistance, two-thirds are in lower-wage jobs, the group says. And in August, Time’s Up announced it had given $750,000 in grants to 18 nonprofits working with those in blue collar industries who’ve dealt with sexual harassment and subsequent retaliation, including a Unite Here local that will be teaching hotel workers in Seattle about their rights.

Informing the most vulnerable workers about their rights is critical. It can be as basic as teaching them what behaviors the phrase “sexual harassment” refers to, says Ramirez of Alianza Nacional de Campesinas.

“Sexual harassment is a legal term of art,” she says, “but when we explain to people what kind of behaviors are considered sexual harassment, then they’re like ‘Oh yes. That happened to me . . . We’ve had women come forward who will say things like ‘I’m being bothered at work.’ Or ‘my supervisor is giving me a hard time.’ “

To get the word out, grassroots groups reach out to farm workers in a number of ways, from having meetings in people’s homes, to doing outreach at laundromats and churches, to skits that act out different scenarios.

“There’s a lot of education required about the legal process,’’ Ramirez says,noting that the remedies can range from an EEOC complaint to filing criminal charges to applying for a “U Visa,” a special document that is an option for immigrants who’ve been victims of crimes like sexual violence or kidnapping. “And some people say I want to keep working at this particular place and this person should be fired,’’ she says.

Ultimately, much of the change is emerging from the grassroots.

“I never thought I would be in this position,” says Kim Lawson, whose sexual harassment complaint against McDonald’s has helped propel her to the forefront of the effort to battle it. “I’ve had a chance to make my voice heard and actually make a difference . .. I’m grateful for the opportunity. I’m grateful for this movement in general.’’ (Charisse Jones, USA TODAY)