A months long investigation uncovered concerns that Cambridge Analytica may have used improperly obtained academic data to craft its psychometric profiles.

In early 2014, a couple years before a bizarre election season marred by waves of false stories and cyberattacks and foreign disinformation campaigns, thousands of Americans were asked to take a quiz. On Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform, where people are paid to perform microtasks, users would be paid $1 or $2 apiece to answer some questions about their personality and turn over their Facebook data and that of all of their friends. A similar request was also distributed on Qualtrics, a survey website. Soon, some people noticed that the task violated Amazon’s own rules.

“Umm . . . log into Facebook so we can take ‘some demographic data, your likes, your friends’ list, whether your friends know one another, and some of your private messages,’” someone wrote on a message board in May 2014. “MESSAGES, even?! I hope Amazon listens to all of our violation flags and bans the requester. That is ridiculous.” Another quiz taker ridiculed the quiz-maker’s promise to protect user data: “But its totally safe dud[e], trust us.”

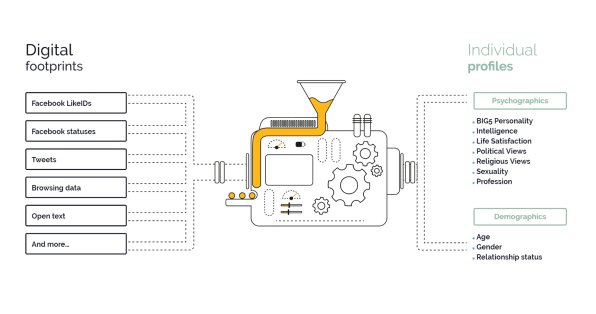

Collecting the data was Aleksander Kogan, a Cambridge University psychology lecturer who was being paid by the political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica to gather as much Facebook data on as many Americans as possible in a number of key U.S. states. The firm, backed by right-wing billionaire donor Robert Mercer, would later claim to have helped Trump win, using an arsenal that included, as its then CEO boasted in September 2016, a psychometric “model to predict the personality of every single adult in the United States of America.” With enough good data, the idea was that Cambridge Analytica could slice up the electorate into tiny segments, microtarget just the right voters in the right states with emotionally tailored, under-the-radar online ads, and–in a very tight election–gain an advantage by, in theory, gerrymandering the mind of the electorate.

Four years and 50 million user profiles later, the data harvest has become the center of a growing firestorm on multiple continents, scaring off users and investors, dispatching lawmakers, regulators, and reporters, and leaving executives at the social network scrambling to face their biggest crisis to date.

Days after exposés by Carole Cadwalladr and other reporters at the Guardian, the New York Times, and Britain’s Channel 4, CEO Mark Zuckerberg took to Facebook to explain how the company was addressing the problem, and to offer his own timeline of events. He said that Facebook first learned of the Cambridge Analytica project in December 2015 from a Guardian article, and that it was subsequently assured that the data had been deleted. But the company offered few details about how exactly it pursued the pilfered data that December. It has also said little about Kogan’s main collaborator, Joseph Chancellor, a former postdoctoral researcher at the university who began working at Facebook that same month. Facebook did not respond to specific requests for comment, but it has said it is reviewing Chancellor’s role.

Concerns about the Cambridge Analytica project—also detailed last year by reporters for Das Magazin and The Intercept—first emerged in 2014 inside the university’s Psychometrics Center. As the data harvest was under way that summer, the school turned to an external arbitrator in an effort to resolve a dispute between Kogan and his colleagues. According to documents and a person familiar with the issue who spoke to Fast Company, there were concerns about Cambridge Analytica’s interest in licensing the university’s own cache of models and Facebook data.

There were also suspicions that Kogan, in his work for Cambridge Analytica, may have improperly used the school’s own academic research and database, which itself contained millions of Facebook profiles.

Kogan denied he had used academic data for his side project, but the arbitration ended quickly and inconclusively after he withdrew from the process, citing a nondisclosure agreement with Cambridge Analytica. A number of questions were left unanswered. The school considered legal action, according to a person familiar with the incident, but the idea was ultimately dropped over concerns about the time and cost involved in bringing the research center and its students into a potentially lengthy and ugly dispute.

Michal Kosinski, who was then deputy director of the Psychometrics Center, told Fast Company in November that he couldn’t be sure that the center’s data hadn’t been improperly used by Kogan and Chancellor. “Alex and Joe collected their own data,” Kosinski wrote in an email. “It is possible that they stole our data, but they also spent several hundred thousand on [Amazon Mechanical Turk] and data providers—enough to collect much more than what is available in our sample.”

A Cambridge University spokesperson said in a statement to Fast Company that it had no evidence suggesting that Kogan had used the Center’s resources for his work, and that it had sought and received assurances from him to that effect. But University officials have also contacted Facebook requesting “all relevant evidence in their possession.” He emphasized that Cambridge Analytica has no affiliation with the University. Chancellor and Kogan did not respond to requests for comment.

The university’s own database, with over 6 million anonymous Facebook profiles, remains perhaps the largest known public cache of Facebook data for research purposes. For five years, Kosinski and David Stillwell, a then research associate, had used a popular early Facebook app that Stillwell had created, “My Personality,” to administer personality quizzes and collect Facebook data, with users’ consent. In a 2013 paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they used the database to demonstrate how people’s social media data can be used to score and predict human personality traits with surprising accuracy.

Kogan, who ran his own lab at Cambridge devoted to pro-sociality and well-being, first discussed psychometrics with Cambridge Analytica in London in January 2014. He subsequently approached Stillwell with an offer to license the school’s prediction models on behalf of Cambridge Analytica’s affiliate, SCL Group. Such arrangements aren’t unusual—universities regularly license their research for commercial purposes to obtain additional funding—but the negotiations failed. Kogan then enlisted Chancellor, and the two co-founded a company, Global Science Research, to build their own cache of Facebook data and psychological models.For the project, Kogan updated the description of his own data-gathering Facebook app to indicate the profiles were being used not for “academic” but “commercial” purposes, he contended last week. But Facebook said his permission to harvest large quantities of data was strictly restricted to academic use, and that he broke its rules by sharing the data with a third party.

Apart from questions over how Kogan may have used the university’s own data and models, his colleagues soon grew concerned about the intentions of Cambridge Analytica and SCL, whose past and current clients include the British Ministry of Defense, the U.S. Department of State, NATO, and a slew of political campaigns around the world. At the Psychometrics Center, there were worries that the mere association of Kogan’s work with the university and its database could hurt the department’s reputation.

The external arbitration began that summer, and was proceeding when Kogan withdrew from the process. At the Psychometrics Center’s request, Kogan, Chancellor, and SCL offered certification in writing that none of the university’s intellectual property had been sent to the firm, and the matter was dropped.

Within a few months, Kogan and Chancellor had finished their own data harvest, at a total cost to Cambridge Analytica—for over 34 million psychometric scores and data on 50 million Facebook profiles—of around $800,000, or approximately $0.016¢ per profile. By the summer of 2015, Chancellor boasted on his LinkedIn page that Global Science Research now possessed “a massive data pool of 40-plus million individuals across the United States—for each of whom we have generated detailed characteristic and trait profiles.”

In December 2015, as Facebook began to investigate the data harvest, Chancellor began working at Facebook Research. (His interests, according to his company page, include “happiness, emotions, social influences, and positive character traits.”) The social network would apparently continue to looking into the pilfered data over the following months. As late as April 2017, a Facebook spokesperson told the Intercept, “Our investigation to date has not uncovered anything that suggests wrongdoing.”

Amazon would eventually ban Kogan and GSR over a year later, in December 2015, after a reporter for the Guardian described what was happening. “Our terms of service clearly prohibit misuse,” a spokesperson for Amazon told Fast Company. By then, however, it was too late. Thousands of Americans, along with their friends—millions of U.S. voters who never even knew about the quizzes—were unwittingly drawn into a strange new kind of information war, one waged not by Russians but by Britons and Americans.

There are still many open questions about what Cambridge Analytica did. David Carroll, an associate professor at Parsons School for Design, filed a claim this month in the U.K. in an effort to obtain all the data it has on him—not just the prediction scores in his voter profile, but the data from which it was derived—and to resolve a litany of mysteries he’s been pursuing for over a year. “Where did they get the data, what did they do with it, who did they share it with, and do we have a right to opt out?”

Meanwhile, special counsel Robert Mueller, who’s investigating possible links between the Trump campaign and Russia, has his own burning questions about Cambridge Analytica’s work and where its data may have gone. Last year, his team requested emails from Cambridge and obtained search warrants to examine the records of Facebook. It also interviewed Trump son-in-law Jared Kushner and Trump campaign staffers, and subpoenaed Steve Bannon. The former Trump adviser was a vice president at Cambridge Analytica from 2014 to mid-2016, when he joined the Trump campaign as its chairman. Former Trump adviser, Lt. General Michael Flynn, who pled guilty in the Mueller probe to lying about his conversations with Russian officials, disclosed last August that he was also a paid adviser to Cambridge affiliate SCL Group.

Cambridge Analytica repeated its claim in a statement last month that it deleted the Facebook data in 2015, that it undertook an internal audit to ensure it had in 2016, and that it “did not use any GSR data in the work we did in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.” Wylie said this was “categorically not true.”

Kosinksi is also skeptical about Cambridge Analytica’s claims. “CA would say anything to reduce the legal heat they are in,” he wrote in an email last November, when asked about the company’s contradictory accounts. “Specifically, Facebook ordered them to delete the data and derived models; admitting that they used the models would put them in trouble not only with investigators around the world, but also Facebook.”

“I am not sure why would anyone even listen to what they are saying,” he added. “As they must either be lying now, or they were lying earlier, and as they have obvious motives to lie.”

Carroll’s legal claim against Cambridge Analytica is based in U.K. law, which requires companies to disclose all the data they have on individuals, no matter their nationality. Carroll hopes that Americans will demand strict data regulations that look more like Europe’s, but when it comes to Cambridge Analytica, given that it appears to store data in the U.K., he believes the legal floodgates are already open. “As it stands, actually, every American voter is eligible to sue this company,” he said.

To Carroll, the question of the actual ability of Cambridge to influence elections is separate from a more essential problem: a company based in the U.K. is collecting massive amounts of data on Americans in order to influence their elections. “In the most basic terms, it’s just an incredible invasion of privacy to reattach our consumer behavior to our political registration,” says Carroll. “That’s basically what [Cambridge Analytica] claims to be able to do, and to do it at scale. And wouldn’t a psychological profile be something we would assume remain confidential between us and our therapist or physician?”

However creepy it may appear, the larger problem with Cambridge Analytica isn’t about what it did or didn’t do for Trump, or how effective its techniques were. Psychologically based messaging, especially as it improves, might make the difference in a tight election, but these things are hard to measure, and many have called the company’s claims hot air. The bigger outrage is what Cambridge Analytica has revealed about the system it exploited, a vast economy built on top of our personal data, one that’s grown to be as unregulated as it is commonplace. By the end of the week, even Zuckerberg was musing aloud that yes, perhaps Facebook should be regulated.

Not A Bug, But A Feature

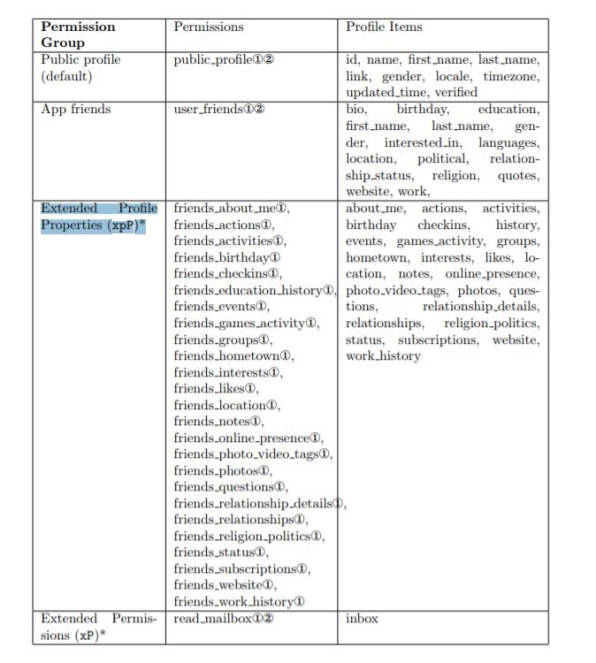

To be clear, said Zuckerberg—in full-page ads in many newspapers—this was “a breach of trust.” But it was not a “data breach,” not in the traditional sense. Like affiliate marketers and Kremlin-backed trolls, Cambridge Analytica was simply using Facebook as it was designed to be used. For five years, Facebook offered companies, researchers, marketers, and political campaigners the ability, through third-party apps, to extract a wealth of personal information about Facebook users and their so-called social graph, well beyond what they posted on the company’s platforms. Carol Davidsen, who managed data and analytics for Obama for America in 2012, took advantage of this feature with an app that gathered data directly from over 1 million users and their friends in an effort to create a database of every American voter, albeit with disclosures that the data was for the campaign.

The policy was good for Facebook’s business, too. Encouraging developers to build popular apps like Candy Crush or Farmville could lead to more time-onsite for users, generating more ad revenue for the company and fortifying its network against competitors. But it was also an invitation to unscrupulous developers to vacuum up and re-sell vast amounts of user data. As the Wall Street Journal reported in 2010, an online tracking company, RapLeaf, was packaging data it had gathered from third-party Facebook apps and selling it to advertisers and political consultants. Facebook responded by cutting off the company’s access and promised it would “dramatically limit” the misuse of its users’ personal information by outside parties.

In its policies, Facebook assures users that it verifies the security and integrity of its developers’ apps, and instructs developers not to, for instance, sell data to data brokers or use the data for surveillance. If you violate these rules. according to Facebook:

Enforcement is both automated and manual, and can include disabling your app, restricting you and your app’s access to platform functionality, requiring that you delete data, terminating our agreements with you or any other action that we deem appropriate.

If you proceeded on the apparently valid assumption that Facebook was lax in monitoring and reinforcing compliance with these rules, you could agree to this policy in early 2014 and access a gold mine.

Sandy Parakilas, a former Facebook employee who worked on fixing privacy problems on the company’s developer platform ahead of its 2012 IPO, said in an opinion piece last year that when he proposed doing a deeper audit of third-party uses of Facebook’s data, a company executive told him, “Do you really want to see what you’ll find?”

Facebook would stop allowing developers to access friends’ data in mid-2015, roughly three years after Parakilas left the company, explaining that users wanted more control over their data. “We’ve heard from people that they are often surprised when a friend shares their information with an app,” a manager wrote in a press release in 2014 about the new policy. Parakilas, who now works for Uber, suspected another reason for the shift: Facebook executives knew that some apps were harvesting enormous troves of valuable user data, and were “worried that the large app developers were building their own social graphs, meaning they could see all the connections between these people,” he told the Guardian. “They were worried that they were going to build their own social networks.”

Justin Osofsky, a Facebook vice president, rejected Parakilas’s claims in a blog post, saying that after 2014, the company had strengthened its rules and hired hundreds of people “to enforce our policies better and kick bad actors off our platform.” When developers break the rules, Osofsky wrote, “We enforce our policies by banning developers from our platform, pursuing litigation to ensure any improperly collected data is deleted, and working with developers who want to make sure their apps follow the rules.”

In his post about Cambridge Analytica, CEO Mark Zuckerberg said that the company first took action in 2015, after it learned of the data exfiltration; then, in March 2018, Facebook learned from reporters that Cambridge Analytica “may not have deleted the data as they had certified. We immediately banned them from using any of our services.”

However, Facebook’s timeline did not mention that it was still seeking to find and delete the data well into the campaign season of 2016, and eight months after it had first learned of the incident. In August 2016, Wylie, the ex- Cambridge contractor, received a letter from Facebook’s lawyers telling him to delete the data, sign a letter certifying that he had done so, and return it by mail. Wylie says he complied, but by then copies of the data had already spread through email. “They waited two years and did absolutely nothing to check that the data was deleted,” he told the Guardian.

Beyond what Cambridge Analytica did, what Facebook knew and what Facebook said about that—and when—is being scrutinized by lawmakers and regulators. As part of a 2011 settlement Facebook made with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the company was put on a 20-year privacy “probation,” with regular audits, over charges that it had told users they could keep their information private “and then repeatedly allowing it to be shared and made public.” The agreement specifically prohibited deceptive statements, required users to affirmatively agree to the sharing of their data with outside parties, and required that Facebook report any “unauthorized access to data” to the FTC. In this case, there’s so far no record of Facebook ever reporting any such unauthorized access to data. The agency is now investigating.

Whatever senators want of Facebook and other data-focused companies, regulations in Europe are already set to change some of their ways. Starting May 25, the General Data Protection Regulation will require all companies collecting data from EU individuals to get “unambiguous” consent to collect that data, allow users easy ways to opt out of giving consent, and give them the right to refuse that their data be used for targeted marketing purposes. Consumers will also have the right to obtain their data from the companies that collect it. And there are hefty fines if any of the regulation is violated, up to 20 million euros.

Getting Out The Vote—Or Not

Like Google, the world’s other dominant digital advertiser, Facebook sells marketers the ability to target users with ads across its platforms and the web, but it doesn’t sell its piles of raw user data. Plenty of other companies, however, do. The famous Silicon Valley giants are only the most visible parts of a fast-growing, sprawling, and largely unregulated market for information about us. Companies like Nielsen, Comscore, Xaxis, Rocketfuel, and a range of anonymous data brokers sit on top of an enormous mountain of consumer info, and it fuels all modern political campaigns.

Political campaigns, like advertisers of toothpaste, can buy personal information from data brokers en masse and enrich it with their own data. Using data-matching algorithms, they can also reidentify “anonymous” user data from Facebook or other places by cross referencing it against other information, like voter files. To microtarget Facebook users according to more than their interests and demographics, campaigns can upload their own pre-selected lists of people to Facebook using a tool called Custom Audiences, and then find others like them with its Lookalike Audiences tool. (Facebook said last week that it would end another feature that allows two large third-party data brokers, Axciom and Experian, to offer their own ad targeting directly through the social network.)

Like Cambridge Analytica, campaigns could also use readily available data to target voters along psychological lines too. When he published his key findings on psychometrics and personal data in 2013, Kosinski was well aware of the alarming privacy implications. In a commentary in Science that year, he warned of the detail revealed in one’s online behavior—and what might happen if non-academic entities got their hands on this data, too. “Commercial companies, governmental institutions, or even your Facebook friends could use software to infer attributes such as intelligence, sexual orientation, or political views that an individual may not have intended to share,” Kosinski wrote.

Recent marketing experiments on Facebook by Kosinski and Stillwell have showed that advertisements geared to an individual’s personality—specifically an introverted or extroverted woman—can lead to up to 50% more purchases of beauty products than untailored or badly tailored ads. At the same time, they noted, “Psychological mass persuasion could be abused to manipulate people to behave in ways that are neither in their best interest nor in the best interest of society.”

For instance, certain ads could be targeted at those who are deemed “vulnerable” to believing fraudulent news stories on social media, or who are simply likely to share them with others. A research paper seen at Cambridge Analytica’s offices in 2016 suggested the company was also interested in research about people with a low “need for cognition”—that is, people who don’t use cognitive processes to make decisions or who lack the knowledge to do so. In late 2016, researchers found evidence indicating that Trump had found disproportionate support among that group—so-called “low information voters.” “It’s basically a gullibility score,” said Carroll.

Facebook’s own experiments in psychological influence date back at least to 2012, when its researchers conducted an “emotional contagion” study on 700,000 users. By putting certain words in people’s feeds, they demonstrated they could influence users’ moods in subtle and predictable ways. When their findings were published in 2014, the experimenters incited a firestorm of criticism for, among other things, failing to obtain the informed consent of their participants. Chief operating officer Sheryl Sandburg apologized, and the company said it would establish an “enhanced” review process for research focused on groups of people or emotions. More recently, in a 2017 document obtained by The Australian, a Facebook manager told advertisers that the platform could detect teenage users’ emotional states in order to better target ads at users who feel “insecure,” “anxious,” or “worthless.” Facebook has said it does not do this, and that the document was provisional.

The company’s influence over voters has also come under scrutiny. In 2012, as the Obama campaign was harnessing the platform in new ways, Facebook researchers found that an “I voted” button increased turnout in a California election by more than 300,000 votes. A similar effort in the summer of 2016 reportedly encouraged 2 million Americans to register to vote. “Facebook clearly moved the needle in a significant way,” Alex Padilla, California’s secretary of state, told the Times that October.

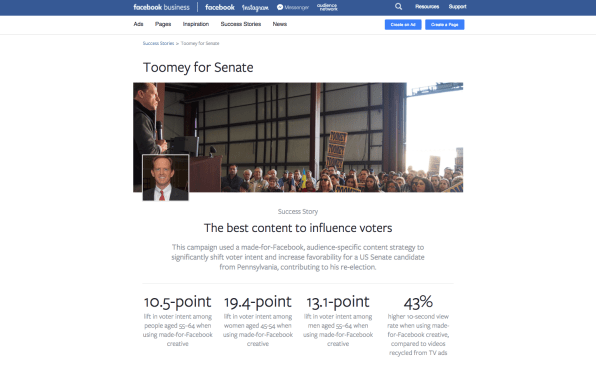

The company has also invested heavily in its own in-house political ad operations. Antonio Garcia-Martinez, a former Facebook product manager, described in Wired the company’s teams of data scientists and campaign veterans, who are “specialized by political party, and charged with convincing deep-pocketed politicians that they do have the kind of influence needed to alter the outcome of elections.” (In recent months, Facebook quietly removed some of its webpages describing its elections work.)

Kosinski, now a professor at Stanford, is quick to point to the power of data to influence positive behavior. In 2010, the British government launched a Behavioral Insights Team, or nudge unit, as it’s often called, devoted to encouraging people “to make better choices for themselves and society,” and other governments have followed suit. As the personal data piles up and the algorithms get more sophisticated, Kosinski told a conference last year, personality models and emotional messaging may only get better at, say, helping music fans discover new songs or encouraging people to stop smoking. “Or,” he added, “stop voting, which is not so great.”Despite an arms race for personal data, there is, however, currently no comprehensive federal law in the U.S. governing how companies gather and use it. Instead, data privacy is policed by a patchwork of overlapping and occasionally contradictory state laws that state authorities and the Federal Trade Commission sometimes enforce. Voter privacy, meanwhile, falls into a legal gray area. While the Federal Election Commission regulates campaigns, it has few privacy rules; and while the FTC regulates commercial privacy issues, it has no jurisdiction over political campaigns. Ira Rubinstein, a professor at New York University School of Law, wrote in a 2014 law review article that “political dossiers may be the largest unregulated assemblage of personal data in contemporary American life.”

The Trump campaign’s own data arsenal included not just Facebook and Cambridge Analytica, but the Republican National Committee Data Trust, which had launched a $100 million effort in the wake of Mitt Romney’s 2012 loss. With the identities of over 200 million people in the U.S., the RNC database would eventually acquire roughly 9.5 billion data points on three out of every five potential U.S. voters, scoring them on their likely political preferences based on vast quantities of external data, including things like voter registration records, gun ownership records, credit card purchases, internet account identities, grocery card data, and magazine subscriptions, as well as other publicly harvested data. (The full scope of the database was only revealed when a security researcher discovered it last year on an unlocked Amazon web server.)

As AdAge reported, a number of Cambridge staffers working inside the Trump digital team’s San Antonio office mixed this database with their own data in order to target ads on Facebook. A Cambridge Analytica representative was also based out of Trump Tower, helping the campaign “compile and evaluate data from multiple sources.” Theresa Hong, the Trump campaign’s digital content director, explained to the BBC last year how, with Cambridge Analytica’s help, the campaign could use Facebook to target, say, a working mother—not with “a war-ridden destructive ad” featuring Trump, but rather one that’s more “warm and fuzzy,” she said.

Facebook, like Twitter and Google, also sent staffers to work inside Trump’s San Antonio office, helping the campaign leverage the social network’s tools and an ad auction system that incentivizes highly shareable ads. (Hillary Clinton’s campaign did not accept such direct help.) By the day of his third debate with Clinton, the Trump team was spreading 175,000 different digital ads a day to find the most persuasive ones for the right kind of voter. After the election, Gary Coby, the campaign’s director of digital ads, praised Facebook’s role in Trump’s victory. “Every ad network and platform wants to serve the ad that’s going to get the most engagement,” he tweeted. “THE best part of campaign & #1 selling point when urging people to come help: “It’s the Wild West. Max freedom…. EOD Facebook shld be celebrating success of product. Guessing, if [Clinton] utilized w/ same scale, story would be 180.”

The campaign would use Facebook in uglier ways too. Days before the election, Bloomberg reported, the Trump team was rounding out a massive Facebook and Instagram ad purchase with a “major voter suppression” effort. The effort, composed of short anti-Clinton video ads, targeted the “three groups Clinton needs to win overwhelmingly . . . idealistic white liberals, young women, and African-Americans” with ads meant to keep them from voting. (In its February indictment, the Justice Department found that Russian operatives had spread racially targeted ads and messages on Facebook to do something similar.) And because they were sent as “dark” or “unpublished” ads, Parscale told Bloomberg, “only the people we want to see it, see it.”

Asked about the “suppression” ads, Parscale told NPR after the election, “I think all campaigns run negative and positive ads. We found data, and we ran hundreds of thousands of [Facebook] brand-lift surveys and other types of tests to see how that content was affecting those people so we could see where we were moving them.”

So far, there is no evidence that Cambridge Analytica’s psychological profiles were used by the Trump campaign to target the “voter discouragement” ads. But in the summer of 2016, Cambridge, too, was tasked with “voter disengagement,” and “to persuade Democrat voters to stay at home” in several critical states, according to a memo written about its work for a Republican political action committee that was seen by the Guardian. Prior to 2007 elections in Nigeria, SCL Group, Cambridge’s affiliate company, also said it had advised its client to “aim to dissuade opposition supporters from voting.” A company spokesperson contends that the company does not wage “voter discouragement” efforts.

While Facebook’s policies prohibit any kind of discriminatory advertising, its ad tools, as ProPublica reported in 2016, allow ad buyers to target people along racist, bigoted, or discriminatory lines. Last month, the company was sued for permitting ads that appear to violate housing discrimination laws.

The company has vowed a crackdown on that kind of microtargeting. It also announced it would bring more transparency to political ads, as federal regulators begin the process of adding disclosure requirements for online campaign messages. But Facebook hasn’t spoken publicly about the Trump campaign’s “voter suppression” ads, or whether it could determine what impact the ads may have had on voters. A company spokesperson told Fast Company in November that he “can’t comment on this type of speculation.”

For David Carroll, tracing the links between our personal data and digital political ads reveals a problem that’s vaster than Facebook, bigger than Russia. The Cambridge Analytica/Facebook scandal could enlarge the frame around the issue of election meddling, and bring the threat closer to home, he said. “I think it could direct the national conversation we’re having about the security of our elections, and in particular voter registration data, as not just thinking in regards to cyberattacks, but simply leaking data in the open market.”

Learning From Mistakes

After election day, some Facebook employees were “sick to their stomachs” at the thought that false stories and propaganda had tipped the scales, the Washington Post reported, but Zuckerberg insisted that “fake news” on Facebook had not been a problem. Eventually, amid a swarm of questions by lawmakers, researchers and reporters, the company began to acknowledge the impact of Russia’s “information operations.” First, Facebook said in October that it had found that only 10 million users had seen Russian ads. Later, it said the number was 126 million, before updating the tally again to 150 million. The company has committed more resources to fighting misinformation, but even now, it says it is uncertain of the full reach of Russia’s propaganda campaign. Meanwhile, critics contend it has also thwarted independent efforts to understand the problem by taking down thousands of posts.

To some, the company’s initial response to the Cambridge Analytica scandal earlier this month echoed its response to Russian interference. Its first statement about the incident on March 16, saying it was temporarily suspending Cambridge Analytica, Kogan and Wylie, and considering legal action, was meant to convey that Facebook was being proactive about the problem, discredit the ex-employee, and get ahead of reporting by the Guardian and the Times, Bloomberg reported. Facebook appeared to use a similar pre-emptive maneuver last November in advance of a Fast Company story on Russian activity on Instagram.

Jonathan Albright, research director at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, who has conducted extensive studies of misinformation on Facebook, called the company’s initial reaction to the Cambridge Analytica revelations a poor attempt to cover up for past fumbles “that are now spiraling out of control.” He added, “Little lies turn into bigger lies.”

Facebook has announced a raft of privacy measures in the wake of the controversy. The company will conduct audits to try to locate any loose data, notify users whose data had been harvested, and further tighten data access to third parties, it said. It is now reviewing “thousands” of apps that may have amassed mountains of user data, some possibly far larger than Cambridge Analytica’s grab. And it announced changes to its privacy settings last week, saying that users could now adjust their privacy on one page rather than going to over 20 separate pages.

The social network has changed its privacy controls dozens of times before, and it was a flurry of such changes a decade ago that led to the FTC’s 2011 settlement with the company over privacy issues. “Facebook represented that third-party apps that users installed would have access only to user information that they needed to operate,” one of the FTC’s charges read. “In fact, the apps could access nearly all of users’ personal data – data the apps didn’t need.” The FTC is now investigating whether Facebook broke the agreement it made then not to make “misrepresentations about the privacy or security of consumers’ personal information.”

After the most recent revelations, Zuckerberg was asked by the Times if he felt any guilt about how his platform and its users’ data had been abused. “I think what we’re seeing is, there are new challenges that I don’t think anyone had anticipated before,” he said. “If you had asked me, when I got started with Facebook if one of the central things I’d need to work on now is preventing governments from interfering in each other’s elections, there’s no way I thought that’s what I’d be doing, if we talked in 2004 in my dorm room.”

Election meddling may have been a bit far-fetched for the dorm room. But Zuckerberg has had plenty of time to think about risks to user privacy. In 2003, he built a website that allowed Harvard undergraduates to compare and rate the attractiveness of their fellow students and then rank them accordingly. The site was based on data he harvested without their permission, the ID photos of undergraduates stored on dorms’ servers.

There was a small uproar, and Zuckerberg was accused by the school’s administrative board of breaching security, violating copyrights, and violating individual privacy. The “charges were based on a complaint from the computer services department over his unauthorized use of online facebook photographs,” the Harvard Crimson reported. Amid the criticism, Zuckerberg decided to keep the site offline. “Issues about violating people’s privacy don’t seem to be surmountable,” he told the newspaper then. “I’m not willing to risk insulting anyone.”

For his next big website, Zuckerberg invited people to upload their faces themselves. The following year, after launching thefacebook.com, Zuckerberg boasted to a friend of the mountain of information he was sitting on: “over 4,000 emails, pictures, addresses, sns,” many belonging to his fellow students.

“Yea so if you ever need info about anyone at Harvard . . . just ask,” Zuckerberg wrote in a leaked private message. His friend asked how he did it. “People just submitted it,” he said. “I don’t know why.”

“They ‘trust me,’” he added. “Dumb fucks.”

Those were the early days of moving fast and breaking things, and nearly 15 years later, Zuckerberg certainly regrets saying that. But even then he had caught on to a lucrative flaw in our relationship with data at the beginning of the 21st century, a delusional trust in distant companies based on agreements people don’t read, which have been virtually impossible to enforce. It’s a flaw that has since been abused by all kinds of hackers, for purposes the public is still largely in the dark about, even today. (By Alex Pasternack and Joel Winston)