“You Hate Me Don’t You.”

During his first solo Grammys performance in 2016, Kendrick Lamar emerged on stage dressed in a prisoner uniform.

Hobbling in lockstep through a cell block, he marched towards a microphone stand – chains chiming beneath reverent horns. As drums blustered in, and “Blacker the Berry” began, Kendrick delivered a message for viewers of the Grammys and the Recording Academy alike: “You hate me don’t you? You hate my people, your plan is to terminate my culture.”

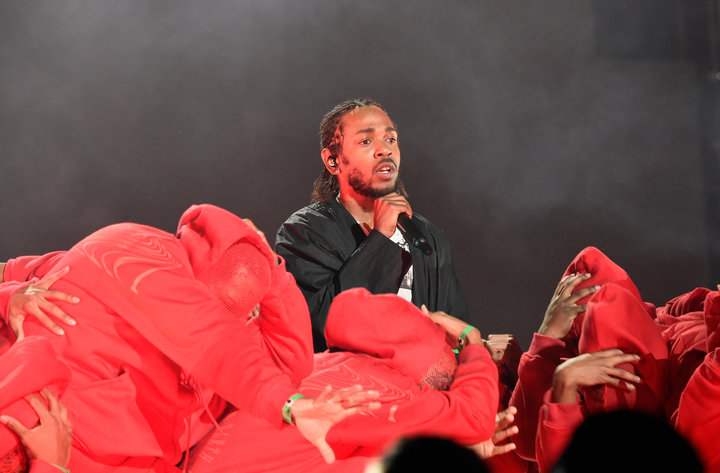

NEW YORK, NY – JANUARY 28: Recording artist Kendrick Lamar performs onstage at the 60th Annual GRAMMY Awards at Madison Square Garden on January 28, 2018 in New York City. (Photo by Christopher Polk/Getty Images for NARAS)

Sunday’s Grammys began with similar incitement. Rife with Americana – from waving flags to a marching military – Kendrick’s opening performance forced viewers to see Black movement and music transposed against their beloved symbols. And as his political theater ended – with gunshots striking Black men by the dozens – viewers were left with a new message, delivered during an interlude from Dave Chappelle: “The only thing more frightening than watching a Black man be honest in America is being an honest Black man in America.”

Following both performances, Kendrick’s honesty was met with rejection for album of the year. And each rejection affirmed Chappelle’s words.

Like “Good Kid M.A.A.D. City” and “To Pimp a Butterfly” before it, “DAMN.” reminded us how hip-hop best tells the truth – with raw reflections on Black America, shared through masterful stories. But for the Grammys, hip-hop’s truths have always proved too tough to swallow.

The Grammys’ relationship with hip-hop is America’s relationship with blackness – a paradox of private obsession and public rejection. Infatuation without acceptance. A perpetual fetish. And while “DAMN.’s” nomination provided an opportunity for redemption, its loss is another mark against an antiquated award show – ever-limited by its unwillingness to truly embrace hip-hop.

On Boycott’s Brink

“DAMN.’s” loss came on the heels of hope. The nominees for album of the year – which featured no white men for the first time in 19 years and two Black hip-hop artists for the first time ever – signaled a shifting perspective for the Recording Academy. More importantly, “DAMN.’s” success was colossal. The Rolling Stone, Billboard, Pitchfork and countless others, named “DAMN.” the best album of 2017 – alongside Jay-Z’s “4:44” – and set the stage for the Grammys’ hip-hop atonement. But when both lost the coveted honor, the Twitterverse exploded with many social media users saying they were ready to boycott the show.

There was no reason to be so surprised. In the last few decades, hip-hop’s general exclusion from album of the year — and all other “mainstream” categories — has become a tired tradition. In 2016, the Washington Post detailed the disparity, pointing out that 421 nominations across those categories have yielded a mere 34 nominations for hip-hop artists — and a single win.

Last year, America’s love for hip-hop and R&B reached its greatest peak yet. For the first time, the two genres – comprising 24.5 percent of all music bought or streamed in 2017 – were America’s most consumed.

While worthy of praise, Kendrick’s dominance of “rap” categories distracts from the fact of hip-hop’s perpetual exclusion. Therein lies the crux of the Grammys’ race problem: the Recording Academy has fallen out of touch with the people they claim to represent.

Such surging adoration for hip-hop – not unlike the rise of Jazz through the Jim Crow era – reveals an American musical paradox. Amid the re-emergence of white supremacy groups and an unabashedly racist president, America’s love for Black music has grown even stronger.

The Hip-Hop Ceiling

When Kendrick dropped “Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City” in 2012, he reminded us how hip-hop best tells stories – laden with hauntingly deft lyrics, too real to remain unfelt. The acclaim for the Grammys-newcomer was staggering, but as history might’ve easily predicted, his seven total nominations that year yielded zero wins.

The most memorable of those losses was to Macklemore for best rap album – the best demonstration of the Grammys’ hip-hop failings. In a moment near-mythical in its constant retelling, Macklemore followed his win with a text to Kendrick, which he later shared via an Instagram image: “You got robbed. I wanted you to win. You should have. It’s weird. I robbed you.”

Kendrick, only becoming more unafraid in his blackness, followed his first album with “To Pimp a Butterfly.” The masterful album that broke streaming records upon release is best thematically defined by “i” – an anthem for unrelenting Black self-love, and “Alright,” the organic anthem for the Black Lives Matter movement.

While themes of Black self-love and self-worth have always been prevalent in Black music and culture, “i” brought that message to a white audience – preceding “Formation,” the dominant track of Beyonce’s “Lemonade”, a song similarly proud of the people it represented. The success of these songs, streamed by the hundreds of millions, marked America’s entrancement with unapologetic blackness – a growing movement of people unafraid to love themselves first.

But for Black folks, loving oneself is a radical concept. Black pride has always been too “militant” to be mainstream. So when “To Pimp a Butterfly” and “Lemonade” were overlooked for Album of the Year, we again found proof of the Grammys’ ― and America’s ― same-old pattern.

’DAMN.’s’ Radical Humanity

If “DAMN.” had won this year’s Grammy for album of the year, its victory would’ve been bigger than merely breaking a pattern. With “DAMN.,” the Grammy Awards missed an opportunity to celebrate an album that defies hip-hop’s critics with radical humanity.

On songs like “FEAR,” Kendrick shares a barrage of childhood realities – from food stamps to social workers to shootouts to police brutality ― and his current realities, which bear more privilege, but also more responsibility.

NEW YORK, NY – JANUARY 28: Comedian Kendrick Lamar performs onstage during the 60th Annual GRAMMY Awards at Madison Square Garden on January 28, 2018 in New York City. (Photo by Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for NARAS)

On ‘DNA,’ Kendrick responds to Geraldo Rivera’s commentary about his music, which he sampled in the song: “This is why I say that hip-hop has done more damage to young African-Americans than racism in recent years.”

But Kendrick does not dignify Rivera’s words with a typical defense. Rather than call out hip-hop’s positive impact on Black people, Kendrick captivatingly rattles off the conflicts “inside [his] DNA” in twos. War and peace. Power and poison. Pain and joy. Millions and riches. Dark and evil. Such a barrage only intensifies as the song progresses. “I know murder, conviction, burners, booster, burglars, ballers, dead, redemption, scholars, fathers dead with kids and I wish I was fed forgiveness.” In sharing this list, Kendrick demands recognition not as a star – but as a mortal man, fallible but worthy all the same.

As Ta-Nehisi Coates has written: “…chief among all individual rights awarded Americans is the right to be mediocre, crass, and juvenile – in other words, the right to be human.” The radical humanity defining “DAMN.” also defines hip-hop, a genre still waiting to be recognized fully.

Kendrick is waiting too. And when he holds a mirror to America, he shows her the bruised backs of those she built her country on. He shows her how poverty damns her people in cycles, and the neighborhoods she built then forgot. He shows her how much love lives there.

“DAMN.” reminds us that hip-hop is America’s music – not because it tells a story America is proud of, but because it takes pride in America’s stories. Stories of imperfect lives, as bound by success as they are by sin. Stories of people hidden in plain sight, daring to be seen.

A.T. McWilliams is a writer based in San Francisco. Follow him on Twitter at @atmcwilliams.