Tears streamed down the face of suicide survivors as they stood on the stage at the Video Music Awards as hip-hop artist Logic performed “1-800-273-8255,” a song titled after the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

The bi-racial rapper, who openly discussed having anxiety, has used his music to address the seriousness of mental health and urge people from diverse backgrounds to seek professional assistance.

“I just want to thank you all so much for giving me a platform to talk about something that mainstream media doesn’t want to talk about,” he said during the VMAs in August.

A history of stigma surrounds mental health, specifically in the black community, and it contributes to the normalization of self-medication and ignoring destructive symptoms, experts say. In 2015, 2,504 blacks died by suicide in the United States, 2,023 or 80.79 percent of which were male, according to a report from the American Association of Suicidology.

“In the black community we sweep those things under the rug, because we just don’t know how to have those conversations,” said Dr. Daphne Watkins, director of the Joint Ph.D. Program in Social Work and Social Science at the University of Michigan.

In recent years, hip-hop has increasingly served as a catalyst for awareness and created a culture that promotes discussion, especially within the black community. Rappers are using social media and lyrics to address their vulnerabilities with fans.

Just weeks after the VMA performance, Logic broke down on stage at Thrival Innovation and Music Festival due to exhaustion, but used that as an opportunity to be transparent with fans.

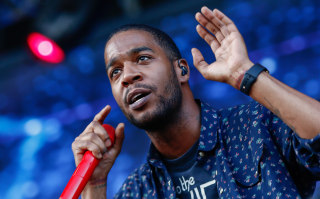

Feeling overwhelmed by depression and suicidal thoughts, hip-hop artist Scott “Kid Cudi” Mescudi announced to fans he was entering rehab in a 2016 Facebook post.

“I am not at peace,” he wrote. “I haven’t been since you’ve known me. If I didn’t come here, I would’ve done something to myself. I simply am a damaged human swimming in a pool of emotions every day of my life.”

Cudi’s hit song “Day ‘n’ Nite”, which was inspired by the 1991 Geto Boys song “Mind Playing Tricks On Me,” described loneliness and depression:

Day and night (what, what)/I toss and turn, I keep stressing my mind, mind (what, what)/I look for peace but see I don’t attain (what, what)

Grammy-nominated hip-hop artist David Banner believes that when rappers publicly address mental health, it enables others to navigate through similar situations, he told NBC News.

“The artist that I would like to say dealt with depression head on more than anybody I have ever heard, was Kid Cudi,” Banner said.

Kid Cudi performs at 2015 Lollapalooza at Grant Park on Aug. 1, 2015 in Chicago. Michael Hickey / Getty Images file

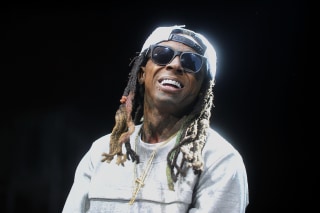

Along with Cudi, several influential artists such as Kanye West and Lil’ Wayne have recounted their mental health struggles through songs in recent years.

Lil Wayne revealed a failed suicide attempt as a feature on Solange’s song “Mad”, which released in 2016.

And when I attempted suicide, I didn’t die/I remember how mad I was on that day/Man, you gotta let it go before it get up in the way/Let it go, let it go

After his 2016 nervous breakdown, Kanye West checked into hospital for treatment. The Chicago rapper has discussed battling depression for years after his mother passed, such as in his 2011 hit “Clique.”

Went through, deep depression when my mama passed/Suicide, what kinda talk is that?

On Jay-Z’s album “4:44,” he discussed having a therapist in the song “Smile,” prompting a dialogue among black men about seeking professional help.

Drug dealers and abusers, America likes me ruthless/My therapist said I relapsed

Banner, also a music producer and actor, has starred in movies such as “The Butler” and “This Christmas.” During a seven year stretch of constantly working, he recalls feeling exhausted partially due to the many demands of his career.

“I was getting only two hours of sleep per night,” Banner said. “The thing was with me being from Mississippi, I never really felt like I had made it. I always felt like my career was temporary. I would work, and work, and work.”

“The God Box” rapper also attributes a great deal of his stress to the pressures of being a black man.

“Name one place where a black man can find mental rest?” he asked. “It’s not the police, it’s not our neighborhoods and it’s definitely not white people’s neighborhoods. It’s no place where we can shut down.”

At the 2013 Hip Hop Awards, Banner participated in a rap cypher and mentioned the suicides of hip-hop moguls Shakir Stewart and Chris Lighty. Both men died from self-inflicted gunshots — Stewart in 2008 and Lighty four years later.

“For two black men to have all of the things that we say we want in life, to commit suicide, this is something we need to address either in public or behind closed doors because there has to be a problem,” Banner said.

Dr. Mark Anthony Neal, professor of African and African American Studies at Duke University, believes black people suffering from mental illness tend not to seek the obvious forms of treatment such as therapy or counseling.

“To see a therapist is foreign to black communities, and especially to black men,” Neal said. “What we see among black men is that they tend to self-medicate, it may be weed, some may be alcohol, and some of it may be pornography.”

Lil Wayne performs during Hot 97’s “Busta Rhymes and Friends: Hot For The Holidays” at the Prudential Center in Newark, New Jersey on Dec. 5, 2015. Brad Barket / AP file

When Banner experienced his worst bout of depression, he said he was willing to try anything within reason to feel better. His mentor introduced him to therapy, and his healing began.

“Therapy, transcendental meditation and clearing my life of toxic situations saved my life and helped me realize the core of my problems were inside of me,” Banner said.

Watkins is also the founder of the Young Black Men Project, which is an intervention that provides support and education about mental health and masculinity. The program, which is facilitated in a private Facebook group, is a safe space where young black men can have an honest discussion regarding their concerns.

“We are trying to dispel these myths by making it manly to know about mental health and seek support,” Watkins said. “You have to want to take care of yourself, and if not for yourself, for your family.” (Courtesy of NBC)