The movement to aid and support New Orleans in the first months after Hurricane Katrina had, of course, a killer soundtrack. In an essay that ran in the New York Times in April 2006, Kelefa Sanneh ticked off a list of high-profile musical efforts that had raised funds for the Gulf Coast after the levees broke: the star-studded “From the Big Apple to the Big Easy” benefit concerts at Radio City Music Hall and Madison Square Garden, several compilation albums, and video montages and jam sessions at that year’s Grammy awards and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremonies.

“Ever since those awful days last year,” he wrote, “the country has been celebrating the rich musical heritage of New Orleans.” Or most of it, anyway. Where, he wondered, were the rappers, the platinum-selling Cash Money and No Limit artists like the Big Tymers, Juvenile and Master P? “Unlike all the other musicians celebrated at post-Katrina tributes,” he wrote, “these ones still show up on the pop charts, often near the top.”

The nationally known rappers Sanneh wrote about hardly ignored their city, before or after it was so badly threatened. They were deeply rooted in local sounds and identity; the title of his essay, “New Orleans Hip-Hop is the Home of Gangsta Gumbo,” was a reference to lyrics on Lil Wayne’s 2005 “Tha Carter 2” album. At the time of Sanneh’s writing, Juvenile’s “Reality Check,” with its Katrina anthem “Get Ya Hustle On,” had just debuted at No. 1. The next month Lil Wayne would drop his “Dedication 2” mixtape, which included the track “Georgia… Bush” – a biting snarl at the Bush administration’s slow response to New Orleans after the floods.

On the street level, 5th Ward Weebie had a runaway local hit with his gleefully rude 2006 single “F— Katrina.” Was the music too gritty to be accepted into the New Orleans heritage canon, Sanneh wondered? Were the artists too overtly successful-looking, with their expensive cars and jewelry (the word “bling,” in fact, was a New Orleans invention) to fit into a preferred narrative of noble poverty for Southern black musicians?

“If New Orleans rappers seem less lovable than, say, Mardi Gras Indians or veteran soul singers, might it be because they’re less needy?” he asked. “Cultural philanthropy is drawn to musical pioneers — especially African-American ones — who are old, poor and humble. What do you do when the pioneers are young, rich and cocky instead?”

****

At about the time Sanneh was writing his piece, Mia X, a top-selling artist for No Limit Records, had traveled to Washington, D.C., to march and speak at a rally on Capitol Hill in support of the many New Orleanians whose lives were upended by the floods. Since 2006, along with rapper and community activist Sess 4-5, she has been an organizer of an annual Katrina-anniversary march that includes rappers, poets, brass bands and speakers. The 10th and biggest-yet edition is set to take place Saturday, Aug. 29, with four brass bands, 12 social aid and pleasure clubs and representatives from the Sierra Club and the national Hip Hop Caucus.

“We have an ignored culture,” she said of New Orleans rap, 10 years later. “And it’s one of the most important cultures, because we really give back to the community – school supply drives, stop the violence rallies, we visit schools. We just do it. Because we are those children.”

“People look for the happy-go-lucky,” in music, she said. “They ignore what hits you in your gut, and at the end of the day, that’s what hip-hop does. But New Orleans is not just the second line – it’s bounce, hip-hop, reggae. It’s the gumbo. And I’m starting to see, they reach out to us a little more now.”

Mia X and her former No Limit labelmate Mystikal are on the bill, alongside Kermit Ruffins, the Pinettes Brass Band and the Wild Magnolias at a fundraiser, Sept. 19 at Tipitina’s, for the New Orleans Musicians Clinic’s new dedicated Big Chief Bo Dollis Memorial Fund, which aids masking Mardi Gras Indians in need. Bo Dollis, Jr., now chief of the Wild Magnolias Mardi Gras Indians, is an old friend of Mia’s. As a child, she masked with the Yellow Pocahontas Mardi Gras Indians, and these days, on second-line Sundays, she cooks and hosts at the Sportsman’s Corner lounge at Second and Dryades streets, a home base for the Wild Magnolias.

That natural overlap between New Orleans rap and more traditional indigenous culture has been a focus of multiple documentary projects over the 10 years since Katrina – an overlap that the Times’ chief pop critic Jon Pareles acknowledged in his review of the late-2005 “From the Big Apple to the Big Easy” Katrina benefit while also briefly noting, six months before his colleague’s “Gangsta Gumbo” piece, rap’s absence from the show.

“New Orleans music,” he wrote, “from jazz to hip-hop (which wasn’t represented at the concert), has a distinctive rolling swing that’s directly derived from community celebrations.”

That feeling of community celebration is what grabbed Matt Miller, a record collector and then-Ph.D. student at Emory University, when he saw DJ Jubilee and rapper Joe Blakk perform at the 2001 Jazz Fest. He’d heard bounce music before, but the live show was something different.

“Seeing bounce in action made it a lot more understandable to me,” he said. “Seeing it in context, even an artificial context like Jazz Fest, I saw how it draws on this New Orleans thing of how to work an audience, how to bring them in and build a relationship with them. That happens everywhere, but in New Orleans it’s taken to a high level, across many genres.”

The next year, he and filmmaker Stephen Thomas started filming “Ya Heard Me,” the first feature-length documentary film about New Orleans bounce. It included both new footage and archival tape from the deep library of John and Goldie Roberts, the producers of the long-running local cable-access show “It’s All Good in the Hood.” The storm delayed the film’s completion. After Katrina hit, the group decided to spend another year revisiting their subjects in the wake of the flood. That steered the film’s focus away from the deep dive into music that Miller and his co-producers intended, but it revealed something else: a community linked by music and energized to preserve it.

****

In the first weeks after Katrina, Preservation Hall was the incubator for the New Orleans Musicians’ Hurricane Relief Fund, which later became the charity Sweet Home New Orleans. The NOMHRF was formed to distribute cash to musicians in immediate need, and later, grew to connect them with housing services, legal advice and other charitable organizations. Jordan Hirsch served as director of both groups.

“The image of what New Orleans music was, at that Katrina moment, was pretty exclusive of hip-hop,” Hirsch said. “Part of it was because the people who are in a position to put on a show at Madison Square Garden at the drop of a hat are necessarily people who are older and well established and came of age a while ago. And they had a sense of what those events should sound and look like, which was maybe out of touch with the people who needed help. But on a certain level, I can kind of accept it, because the people who are in a position to write checks are probably of that status also.”

Hirsch, who was 24 in 2005, had grown up listening to bounce music in the ’90s. He knew that not all New Orleans rappers – not even all well-known and popular New Orleans rappers – were, as Sanneh wrote, “rich and cocky.”

“We tried to keep the funnel as wide as possible for assistance,” he said. Sometimes that meant working harder to reach out to musicians who fell outside the accepted canon of traditional New Orleans music, including hip-hop and bounce performers. The standards for receiving aid through NOMHRF or Sweet Home were deliberately broad. A musician simply had to have been a working professional in New Orleans at the time the levees broke. In 2005, before social media use was ubiquitous, word of mouth was the best strategy for reaching those in need, and Hirsch found that rappers (as well as other non-“traditional” musicians, like punk-rock or heavy metal bands) were “trickier” to reach, he said, because they weren’t already plugged into the networks that connected so many local musicians to those with the resources to help: WWOZ, Offbeat magazine, Jazz Fest.

“But we tried to let people in the community know that people could apply,” for aid, he said, “and we tried to do the legwork to put the resources to work in a wider way.”

***

In 2008, a year after the New Orleans premiere of “Ya Heard Me,” Holly Hobbs moved to New Orleans to begin a Ph.D. program at Tulane. She eventually planned her dissertation on the topic of hip-hop and bounce in New Orleans after Katrina, and the music’s role in shaping community in the face of disaster.

“But dissertations, generally speaking, are not widely accessible,” she wrote in an email. In 2012, she began collecting lengthy video interviews with rappers into a body called the NOLA Hip-Hop Archive, which is now housed by the Amistad Research Center on Tulane’s campus and online. She prioritized making the archive project a part of the community it documented, inviting rappers to take over its Twitter account and hosting concerts, such as a collaboration between Preservation Hall’s new brass ensemble, PresHall Brass, and rappers Fiend and Nesby Phips in February 2015.

Hobbs cautioned in the email conversation that as a recent transplant, she preferred not to make global generalizations. But based on her 50-plus interviews since 2012, she wrote, “what many of these musicians say backs up my own experience, which is that Katrina really seemed to accelerate the movement of New Orleans rap and bounce toward what we might call the ‘New Orleans Traditional Music Canon.'”

“There are still many, many issues, but rap and bounce are now in spaces that they simply were not a few years ago. We can see this to the greatest extent with ’90s bounce — I see it as being generally accepted now as yet another ‘sound of New Orleans.’ That’s a big change from the past.”

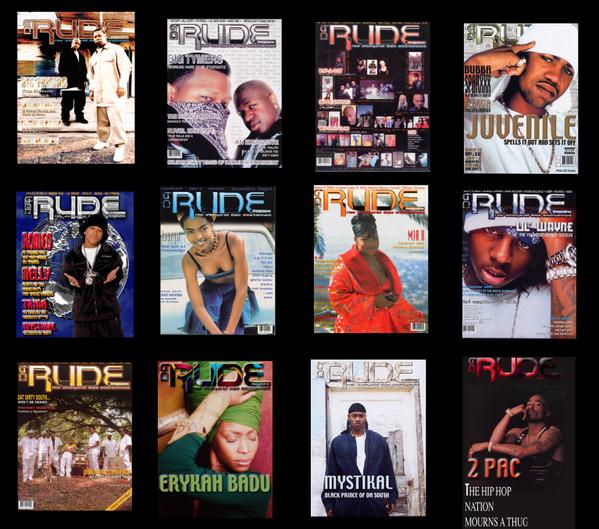

Hobbs’ assessment echoed something I wrote myself in the catalog essay for “Where They At: New Orleans Hip-Hop and Bounce in Words and Pictures,” a multimedia exhibit that appeared at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in the spring of 2010. The exhibit was a selection from a larger body of my own long audio interviews conducted over the two years prior to its opening; portrait photos and performance video by the photographer Aubrey Edwards; archival images from nightclub photographer Sthaddeus “Polo Silk” Terrell; and records, tapes, CDs and ephemera from multiple collections, including that of Loren Phillips Fouroux, who in the 1990s published the first New Orleans rap-focused magazine, “Da R.U.D.E.;” and Offbeat magazine, which at the same time had run a column by Q93.3 program director Karen Cortello that kept up to date with goings-on, locally, in that industry.

“Where They At,” now archived online at wheretheyatnola.com, was eventually exhibited in several cities in the U.S. and Europe, as well as in capsule form on the Jazz Fest grounds in 2010. It, and the Hip-Hop Archive project – interviews from “Where They At” and “Ya Heard Me” soon will be available as part of the Archive’s collection – were only part of the renewed interest in New Orleans rap as a whole after Katrina.

Miller published the scholarly work “Bounce: Rap Music and Local Identity in New Orleans” in 2012. The year before, I co-wrote “The Definition of Bounce: Between Ups and Downs in New Orleans” with veteran performers and promoters Tenth Ward Buck and Lucky Johnson, who went on to produce a community theater production of the same name. In his 2013 book “Roll With It,” Tulane music professor Matt Sakakeeny made explicit connections between local hip-hop and the evolution of New Orleans brass bands. At their monthly industry event “Industry Influence,” which began in 2007, Q93.3FM DJ Wild Wayne and recording artist Sess 4-5 booked frequent panel discussions examining the history of local hip-hop and bounce.

As Big Freedia’s star rose internationally, he often used the spotlight to raise awareness of the regional music he’d grown up in, from booking guest stars like early influencers the Show Boys at the 2014 Voodoo Experience – whose 1986 song “Drag Rap (Triggerman)” is a cornerstone of the sound – to including deep historical background in his 2015 memoir. Earlier this year, the boutique art magazine publishers Cashew Co. dedicated a thick, glossy journal to New Orleans, with multiple interviews with local rappers and vintage photos from Terrell.

After leaving Sweet Home New Orleans, Jordan Hirsch went on to work as a consultant and, in its third season, as a writer, for HBO’s post-Katrina New Orleans drama “Treme,” which employed hundreds of local musicians. The program was inspired in part by the local musician Davis Rogan, on whom the “Treme” character Davis McAlary was based. Before Katrina, Rogan had infamously been fired as a volunteer DJ on the community radio station WWOZ for playing bounce music – specifically, Cheeky Blakk, who worked as a nurse to supplement her musical income.

Between the efforts of Rogan, music consultant Don B – an accomplished local rap producer and engineer who is also the son of Dave Bartholomew – and Hirsch, Blakk appeared on “Treme,” as did Juvenile, Mannie Fresh, Katey Red, Big Freedia and Sissy Nobby. On “Treme,” a multifaceted presentation of what New Orleans music was went out around the world, and hip-hop and bounce were included. And more than 10 years after DJ Davis was booted from WWOZ’s airwaves for playing bounce, early discussions about an online-only “WWOZ-2” streaming channel floated the idea of a show focusing on bounce music. (It was two ‘OZ personalities, in fact, show host Brice Nice and music director Scott Borne, who formed a label to reissue the music of the well-loved bounce pioneer Ricky B in 2013.)

There are plenty of reasons for rap to take longer to embed itself in the canon that have little to do with Katrina, and the biggest is simply time. At the time Sanneh was writing, and as he mentioned himself, early hip-hop in general was just beginning to receive the validation that had long been granted to jazz, rock n’ roll and blues: museum exhibits, collections at university libraries and scholarly work. Because of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s mandate that 25 years must elapse between an artist’s first recording and eligibility for induction, in 2006, the first rappers were only just making their way onto that ballot, and Southern rap had emerged later than the genre’s New York pioneers.

In “Gangsta Gumbo,” back in 2006, Sanneh theorized that perhaps the sound was still too young and too immediate to be canonized. Even the music of Louis Armstrong, he pointed out, was once considered edgy and dangerous to polite society.

“A quarter-century from now … they may find themselves honored in just the kinds of musical tributes and cultural museums that currently shut them out,” he wrote.

“Perhaps, like so many other pop-music traditions, ‘gangsta gumbo’ is a dish best preserved cold.”

It’s true that time tends to confer gravity and respectability. But in New Orleans, a city that thrums to the sound of its streets – and in a way, preserves its soul in that sound – something more was going on.

“When (New Orleans culture’s) continuation was in question, that prompted deeper thinking about it,” Hirsch said. “There was more attention paid to the interconnectedness of traditional New Orleans culture, and with hip-hop, it became hard to sustain the fantasy that it wasn’t involved.”

In the weeks and months and even years after the levees broke, New Orleanians confronted the fear that the culture that is so much of who we are was in danger. In the effort to preserve it, we were forced to work harder to define it, and in that process, we may be finding that we are bigger, more manifold and more diverse than we imagined. (By )