Every day, Kelly Patchett takes a tub of green cannabis-infused coconut butter down from her pantry.

Sometimes she rubs it directly onto her aching skin. Other times she blends the butter into mashed potatoes, makes cannabis chocolates, or bath melts with essential oils and epsom salts.

When the pain’s really acute, or at night before she goes to bed, she smokes the plant raw.

For years the Nelson woman woke up with whole-body pain that sears across her shoulders, back and hips.

She used to live on a precarious cocktail of drugs: opiates, antidepressants and sleeping pills just to get her through the days and nights, after being diagnosed two years earlier with the musculoskeletal disorder, fibromyalgia.

Her two children, 3 and 5, know about “mummy’s green medicine” and not to touch it; even her doctor supports her cannabis use, having seen her quality of life improve.

Six months ago, the 39-year-old was mostly confined to home and unable to drive.

“I had been going up and up in my opiates to the point where I was on a borderline amount and my doctor was looking at sending me to the pain clinic and applying for stronger medication,” she says.

“I was in such a bad place mentally; everyday I was on the edge of taking the maximum amounts of opiates you can without having a cerebral seizure. I would think about my children and [I was] frightened.”

Patchett knew she couldn’t continue living the way she was. So she did what so many sick New Zealanders around the country are doing as an alternative: she turned to cannabis.

After six months Patchett tapered off all her prescription medication and replaced it with a daily supply of medicinal marijuana.

As New Zealand continues to debate whether or how far to relax laws around cannabis use, sufferers like Patchett are preferring action, not words.

But is their faith justified? Just how does the cannabis plant actually work in the human body?

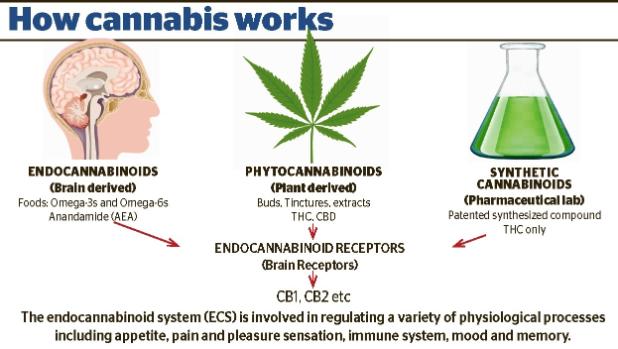

Scientists have only relatively recently discovered the neurotransmitter system triggered by cannabis.

Named after the plant that led to its discovery in the 1980s, the “endocannabinoid system” is thought to regulate a range of functions including mood, memory, pain, sleep, immune function, inflammation, motor control, appetite, digestion and more.

It’s believed the widespread physical and psychological effects of cannabis work by targeting the endocannabinoid system in the body.

Otago University endocannabinoid researcher Dr John Ashton says cells in the body communicate in different ways, and the endocannabinoid system is just one of those ways.

While cannabis has over 100 compounds — called cannabinoids — the two most well-known are the psychoactive one, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and its non-psychoactive counterpart, cannabidiol (CBD).

THC makes you feel high, while CBD doesn’t; it has no psychoactive effects.

“When a person takes THC, all of the cannabinoid receptors in the brain are activated at once,” Ashton says.

There are different receptors in the brain which respond to different cannanoids, but some can interact with both.

For these reasons, scientists are trying to use different cannabinoids to see if they can target certain health conditions.

While they have sorted out the basics, much remains to be uncovered.

Put simply, cannabinoids from the cannabis plant communicate with the body and tells the functions, such as pain, motor control and appetite etc to either move or stop.

THC is known to have a moderate effect on pain, about the same as a dose of codeine, Ashton says.

But there was a gap between what some people in cancer care reported and the “underwhelming” clinical trial evidence.

“People still say that it ‘makes them feel better’ – this may be because of the mood-altering and sedative effects of cannabis as well as mild pain relief,” he says.

Evidence for pain relief from CBD was even weaker, but it had shown to reduce the number of seizures in children with epilepsy.

But the evidence wasn’t all positive.

“It’s quite a different matter when talking about people in cancer palliative care using cannabis, as opposed to general cannabis liberalisation,” he says.

“By analogy, opioids are used medically for certain indications, but when potent opioids become widely available there are problems, as in the situation in USA today. Cannabis obviously isn’t the same league as strong opioids, but it isn’t without harm either, especially for younger heavy users.”

Auckland University molecular pharmacologist Dr Michelle Glass is researching whether cannabinoid compounds alter brain cancer cell growth or migration.

It’s still early days, but Glass says she hasn’t seen evidence of robust cancer cell death yet.

“We weren’t really expecting to though, as if it was that simple the endocannabinoids would kill the cancer and the tumours would never form.”

Glass says a US review on the studies of medical cannabis found strong evidence for benefit in chronic pain, nausea and spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis (MS), particularly for oral cannabinoids.

The study also uncovered evidence for harm around smoked cannabis in respiratory conditions, low birth weight babies following maternal use during pregnancy, impairment of cognition, development of psychosis and increased motor vehicle accidents.

Fifth year Otago University medical student Tori Catherwood is “alarmed” at New Zealand doctor’s ignorance about cannabis and the endocannabinoid system, which she says is barely taught at medical school.

Catherwood is producing a cannabis documentary aimed at the medical community and runs a private Facebook group, Medical Students for Medicinal Cannabis, with 155 members.

For Catherwood, the fight to relax medicinal cannabis laws for sick is a battle close to home.

After her mother was diagnosed with terminal breast and lung cancer, she observed the “miraculous” changes to her mother’s well-being after she started using the plant.

It allowed her to significantly decrease her dependency on pain medication and to sleep, eat and gain weight.

Catherwood says she watched patients asking their doctors about using cannabis for health conditions known to benefit from it, and the doctors would actively discourage the use, or say they didn’t know about the studies.

“The cannabinoid receptors are the most numerous receptors in the brain,” she says.

“As a medical student with a Masters in cell and molecular biology, this seems pretty important to me and suggests that the endocannabinoid system’s role in the human body should be highlighted to these influential future doctors, who will be using [prescription] drugs daily that interact with the endocannabinoid system.

“If they don’t know, they are unknowingly causing harm,” she says.

So while campaigners keep crusading and scientists toil to understand cannabis and the system named after it, the war on drugs wages relentlessly on.

Scientific evidence for its possible health benefits seems somewhat mixed, but today thousands of Kiwis will light up a joint illegally, claiming it improves their quality of life.

It’s getting late. Patchett sits outside while her children sleep soundly indoors.

She crumbles a small cannabis flower into a cigarette paper, before licking the gluey stripe and beginning her bedtime routine of self-medication.

Tonight, she will sleep well.

“How would my life be different if cannabis were legalised?” she says.